Whatever doesn’t kill you, makes you stronger.

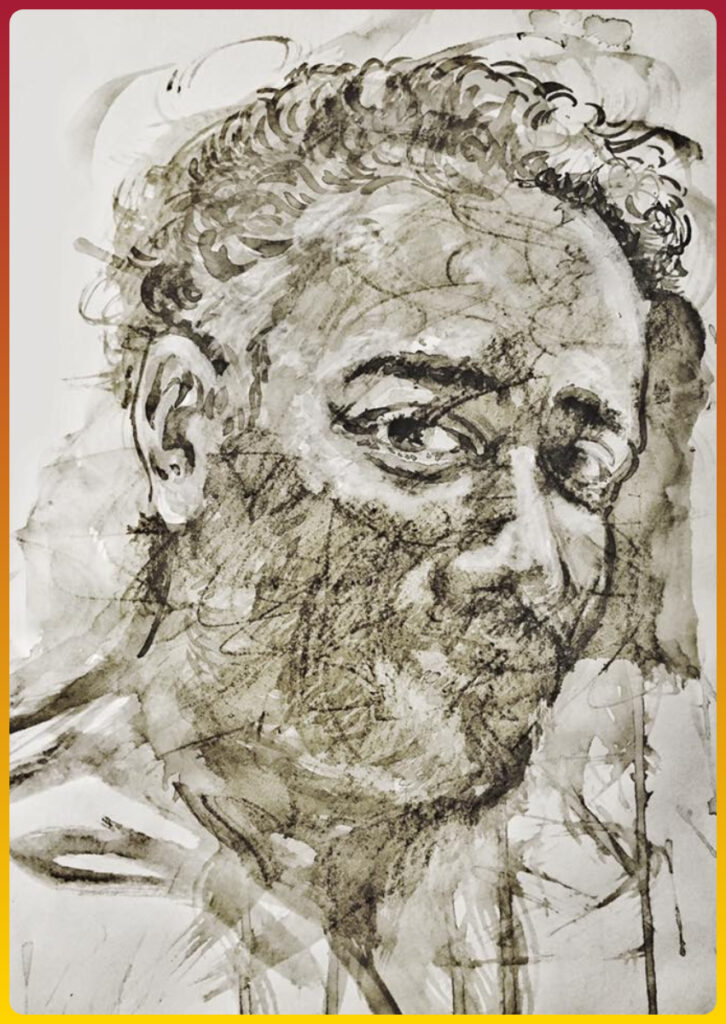

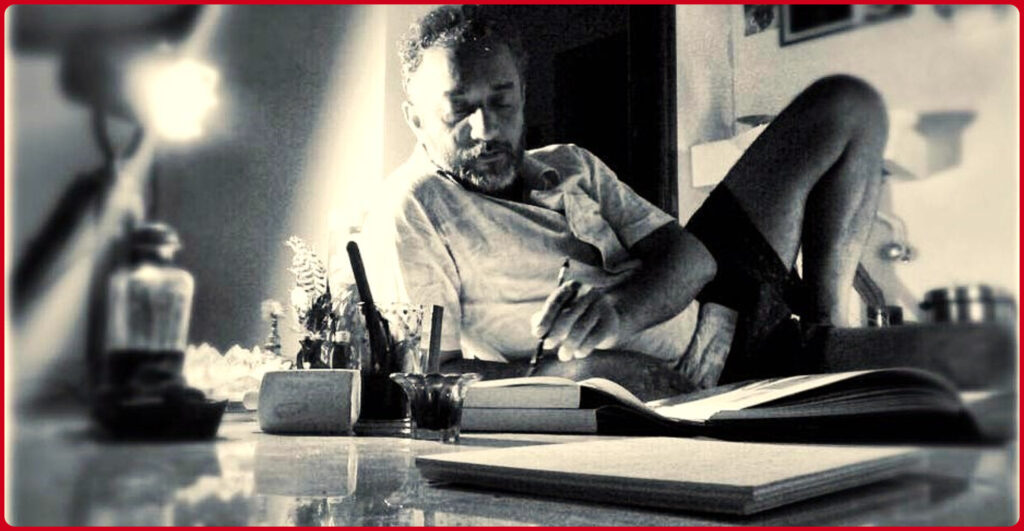

That saying goes rather well with Art Director Sukant Panigrahy – one of the most quirky yet dependable professionals in contemporary Hindi film industry. He came. He countered. He conquered. But he also stayed true to himself, and that’s what makes him distinct.

We have covered the beginning of his amazing journey in the first edition of this two part blog, till the time Sukant landed his first independent feature film project as an Art Director – Prakash Jha’s ‘Gangajal’.

I certainly have a feeling that to do justice to the twists and turns of his journey, I might need to write an entire book. I can only say it’s tough to do that without sponsors, and continue to earn my sustenance at the same time. Believe me, I tried and I know.

I did start the process of writing a book on Mulchand Dedhia, India’s first and foremost Gaffer, even interviewed him for 10 days – but have not been able to complete the project yet. I will do that book for sure, but yes, it will still take some time.

So no more tall claims, as of now.

Here I will focus only on the key turning points of Sukant’s journey, things that have shaped his unique personality and artistic craft. Even then, statutory warning – this is long-format writing. In this case – it might become extra-long.

After working on Gangajal, things became slow for Sukant. Couple of days of work in a month, or maybe three days, just enough to keep the ball rolling. When the film was finally released, it caught the fancy of viewers. As a result, Sukant started getting offers as an art-director, but by then he wanted to get away from it all.

Now, Sukant wanted to make his own movies.

At the same time, Helen Jones, an Australian film-making aspirant with an art and cinema background came to his life. Helen had worked on films in her native country as well as acted in Hollywood films. Despite being quite older than Sukant, her unique perspective on cinema appealed to Sukant. They met, they continued to talk, and soon became a team.

That was when Sukant decided to go back to Odisha. He wanted to make films in Odia – tell the stories of his own people, culture.

Sukant shelved his directorial dreams for a while.

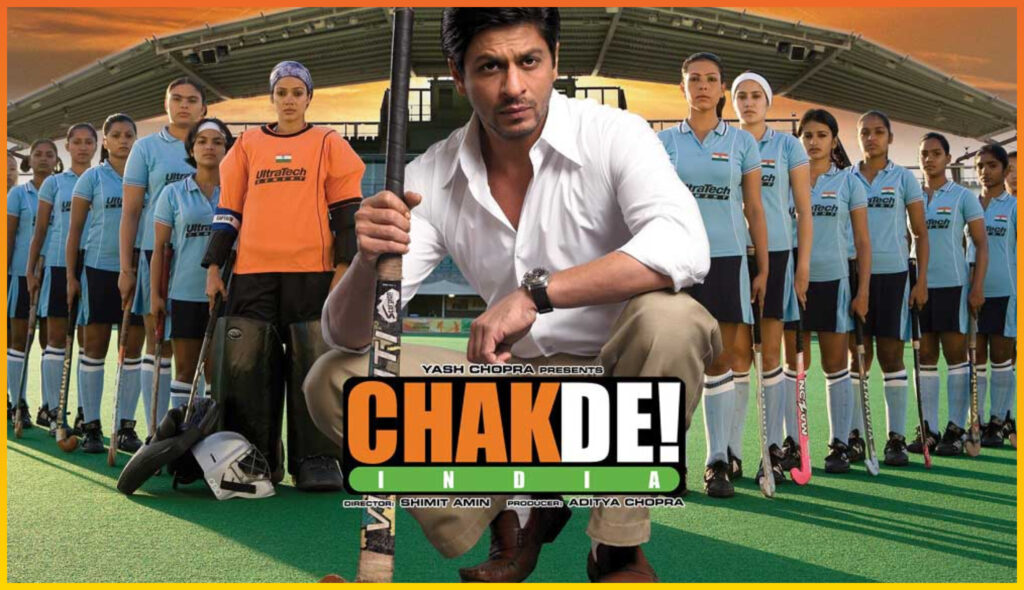

Since people had appreciated his work in Gangajal, he started messaging everyone he knew. Shimit Amin’s team responded. Shimit had already done ‘Abtak 56’ and he was looking for an art-director for his latest sports drama. For this – he wanted a raw and rugged feel, not the polished Sharmistha Roy kind of look.

That Aditya Chopra project came to Sukant. It was ‘Chak De India’.

All of these were sets!! I was genuinely surprised to know that.

When Chak De India was just about to end, Sukant got a lifetime opportunity to work in a Wes Anderson film – ‘The Darjeeling Limited’.

Working with Wes would be a dream come true for any production designer. But at that time, Sukant didn’t know that. Anderson’s team came to Sharmistha Roy, but she was not available. She recommended Sukant’s name. He went to Delhi, held meetings, and then started working on the project. By then he had seen all his earlier films and realized that Wes gave utmost importance to production design. Obviously, Sukant was excited.

He shared this excitement with others on the set of Chak De India.

I believe that might have been a mistake.

Yashraj is good with extravaganza. Thanks to his stint with Sharmistha, the ‘spectacular’ had also become Sukant’s forte. That apart, Adi had trust on him. Besides his own fees, Sukant always spent money according to a plan, and kept all his accounts transparent.

That was also the time when DEV-D entered his life.

Sukant was also a bit tired doing similar kinds of films, so a cheeky retelling of the Devadas mythos came to him as something fresh and unique.

By then, Sukant had seen a few scenes of Anurag Kashyap’s ‘No Smoking’. And yes, he did see ‘Black Friday’. Sukant told me that he really liked Anurag’s film-making sensibilities. It was evident that Anurag was trying to do something in a different space – and he had made a name for himself doing that.

This sense of humility and inability to forget his roots is what makes Sukant stand out in the crowd of Hindi Cinema’s who’s who. This is what makes him special – this innate urge to help others. This urge had stayed all along, coming to the surface often.

Let’s go a little back in time. Even while working under Sharmistha, during the times of ‘Dil Toh Pagal Hai’ – Sukant had joined a theatre group. Mostly because he didn’t have a friend circle in Mumbai at that time.

The director of that group Amarjeet Amle hosted major plays, of Dharamvir Bharti and others. From that group, Nirmal Pandey and Saurav Shukla became key entrants into the film industry – rest there were others too.

But Sukant remembers the experience for entirely different reasons.

Yet another day. Yet another chance encounter.

Working with M F Hussain became a key turning point of Sukant’s life. That was when he started thinking of himself as a potential artist rather than just an art-director in films.

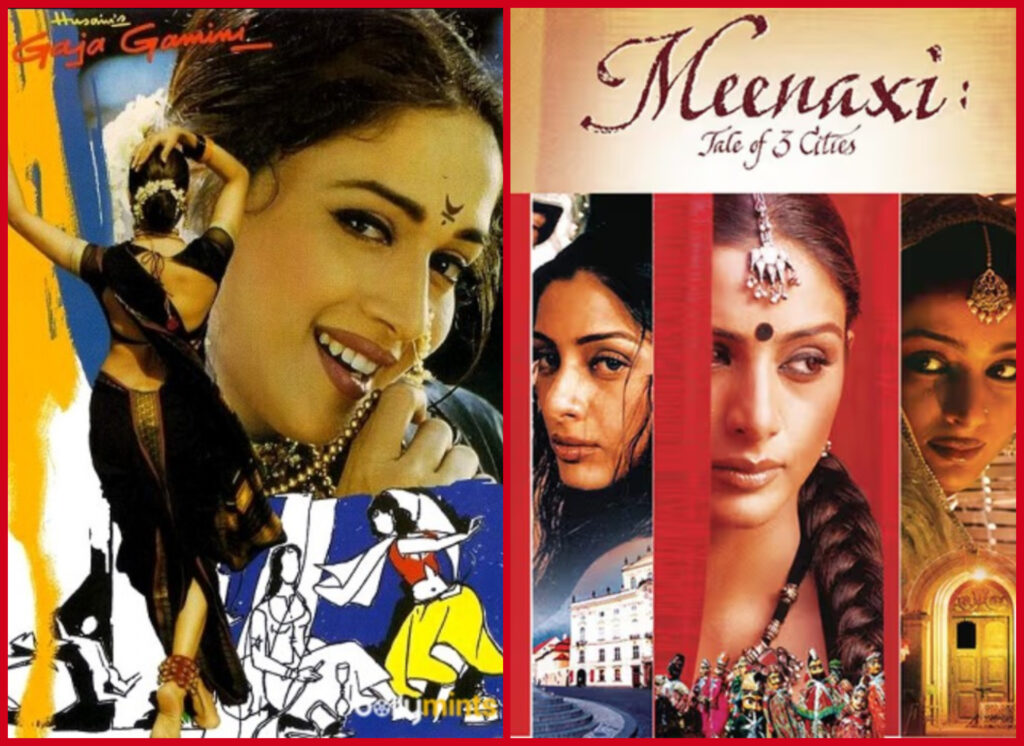

Sukant’s mentor Sharmistha Roy was the Production Designer for both M F Hussain films – ‘Gaj Gamini’ and ‘Meenaxi’. Since both were art-heavy, she trusted Sukant to do the major work. In the process, he got the chance to see ‘Hussain sir’ working – up-close and personal.

That was when Sukant started thinking beyond cinema.

He now wanted to explore other artistic domains like installations and sculptures – so he approached the Kala Ghoda Festival organizers in Mumbai. For that festival, he came up with this idea of making a huge black horse out of scrap material and waste.

That Black Horse was hugely appreciated. It was a genuine crowd puller, and the jury members of the festival were very impressed, which they mentioned without any qualms.

Sukant continued doing numerous sculpture and installation-art out of trash material.

People appreciated them, and he started earning respect as an artist. That was also when he started looking for a place to set up his own community art-studio. Somewhere from where he could contribute to the society through his work, his practice.

While doing the VFX course in Chennai, Sukant visited Auroville a few times. Auroville blew his mind. The architecture, the lifestyle, the community living – that got inside him. Since then, he always wanted to create his own such retreat – a space for his creative impulses, modelled on the manner of Auroville, but without its religious cadence .

We sat on the first floor of this for the interview.

Sukant wants people to start rethinking on habitation. He built this house just to prove that such ideas are possible. Environmental degradation has always been a major concern for Sukant – perhaps due to his early rural roots. All his major artworks, including his installations made out of waste, express this worry.

He is afraid of the indifference of people when it comes to contributing for the environment. His concern is genuine – there has been so much of talks about pollution and global warming, everyone seems to be afraid of a dystopian future without natural resources and we are making countless films about it – but what are we really doing about it?

Among all these what piqued my interest was Sukant’s continued efforts towards telling his own stories – as a writer-director.

It’s not that he didn’t try. Some films were shot around 80%, others 50%, some 10% – but none of them reached completion, for reasons beyond his control. Till the time the lockdown came, Sukant has tried seven to eight times to make his own film.

I can’t get into the details of the short film which I have seen and enjoyed – since it is still being privately sent to festivals around the world. All I can say is its a simple and heartfelt story of childhoods that lack identity, and impositions that doesn’t make sense wherever they are.

No wonder Sukant liked the story.

Even if he doesn’t make a single feature film of his own, Sukant Panigrahy will very well be remembered for the person he is, and for the respect he has garnered from the underprivileged within the film industry. Not everyone has the guts to stand against the colossal might of the producers, especially when those same producers gave him work.

During his long stint in the Mumbai Film Industry, Sukant Panigrahi didn’t like the way the labour unions functioned. Unlike many others who might have had the same feeling, he decided to do something about it.

This engagement had a huge backlash on Sukant’s career, which still continues. All of a sudden, producers who had lot of trust on Sukant, started avoiding him. This had nothing to do with his work. Sukant firmly believes that the stamp of being a ‘union-leader’ alienated him from the producers, who started feeling threatened.

Naturally, since his fight was against them.

If he saw something wrong on the sets , he used to point it out then and there. Producers didn’t like that. They would rather work with less vocal people.

Sukant willingly stirred the hornet’s nest. And that stung him back.

Sukant now feels that despite his sincere attempts, things haven’t changed much.

There has been an increased awareness, but people who could actively make a difference are not interested in union work. It’s somewhat similar to the way normal people look at politics. People would like to comment on it, criticize it, but when it comes to joining it to make some real changes happen – they have an acute aversion towards active involvement.

For me, Sukant comes across as strange.

How can someone follow his heart wherever it takes him, always choose the rough terrain despite being mostly barefoot, without caring about the repercussions? How can someone not just keep his senses alive but keep enhancing them, enduring obstacles at every stage?

That’s strange, isn’t it? That’s what crazy looks like to us who are used to compromise our dreams for life’s little conveniences.

Sukant stood for what he believed in. He consciously did things just because he thought it was his duty to do them. He took roads that led to his own isolation.

Who does that? Will you?

For me, I believe it’s rather difficult to be Sukant Panigrahy.

It’s been a long interview.

But I couldn’t possibly end it without asking my customary last question, can I?

For my young friends, I always try and ask stalwarts in the industry about how to follow in their footsteps. And as far as Sukant is concerned, he loves interacting with young and fresh minds. He goes to Subhash Ghai’s school Whistling Woods from time to time – as a visiting faculty. There he teaches direction students about Production Design. He also goes to FTII, NID and NSD among other eminent institutes. Many students there, especially those with artistic inclinations, want to get into the field of art-direction.

I asked Sukant, from the perspective of a greenhorn (which I am) – in case I want to become an Art-Director/Production Designer in the film industry, how do I go about it?

Faith is a good thing to have on yourself. And hope.

Once these emotions do not make sense anymore, life loses a fair share of its meaning and substance. Sukant understands that. He knows, hope that you give gets back at you . In a very miniscule and humble way, I believe in that too.

Dear readers, I did want to present this blog in the new year. That didn’t happen, and I will not blame myself entirely for that. Neither will I blame anybody else, including circumstances. On the other hand, yes, I do want to make some course corrections now.

Somehow, close to 70 people are reading this blog everyday. I don’t know how the fish that’s happening – but if you have really had the patience to reach till here, I would rather want to share my new year’s resolution . Last year, I managed to do only two blogs – on Hitendra Ghosh and Sukant Panigrahy. I would say that is a bit too less considering the money Bluehost and GoDaddy charges me annually.

This year I am going to change that. Let’s try one in a month, at least. And that book.

Do you like Bollywood dancing? If you do, prepare for a feast.

For now, I leave you with an interview. For Sukant, enough is nothing.

Be First to Comment