Sometimes, an idea gets stuck in your head. It’s like that fragment of a tune or those staggered images that continues to play in a loop – and refuses to budge unless you do something with it. A musician will probably create a symphony out of it; an artist will paint his heart out; a performer will throw it at his audience.

For me, I write.

Gautam Chatterjee’s Videogaan is like that chord progression stuck in my head.

I have to write about it, to move on.

I have already told you, in part one of this blog, that Videogaan was a series of music videos shot for Calcutta Doordarshan in 1995. Which makes it roughly a year before MTV came to India, and much before the concept of Bangla Band became a neighborhood craze. There wasn’t much of a local reference to follow and the whole exercise was a limited budget affair; hence everything was freshly thought and implemented, from the scratch.

I really don’t know if those videos, shot in U-matic if I remember it right, are still lying in Kolkata Doordarshan archives; extremely unlikely.

But in spite of the fact that not many have seen them, I would like to talk a bit about them here, while remembering Gautamda. I do have a distinguished line up of his students from SRFTI, but this happens to be my blog, so I get the first chance to speak.

I start with a set of pictures that Minoti boudi shared with me, from the shoot of Videogaan. This should ignite some fond recollections.

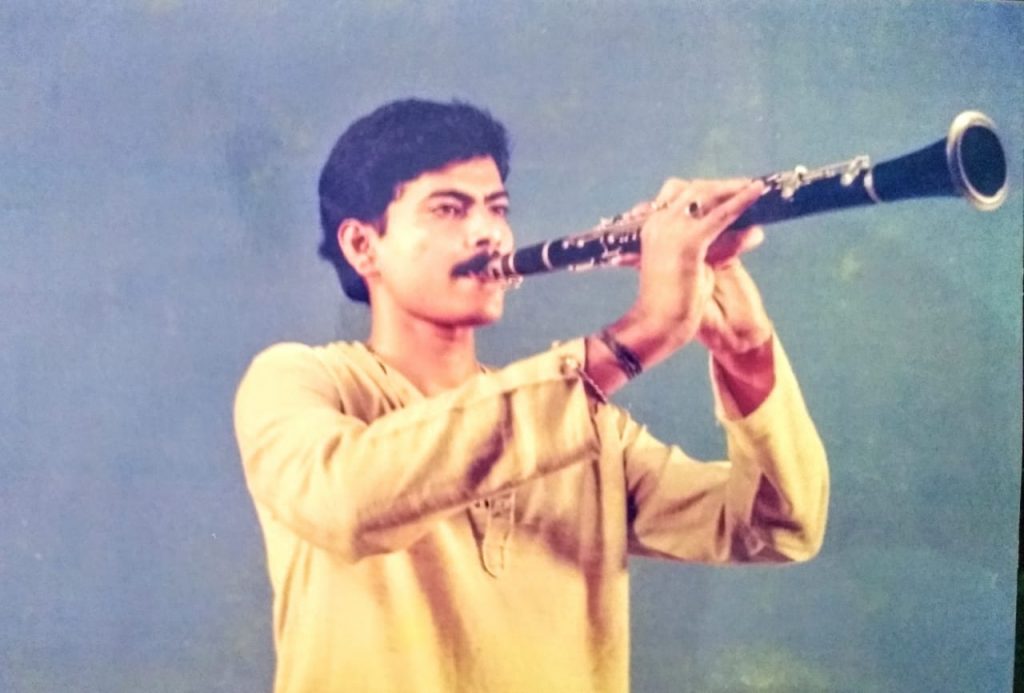

If I joggle my memories, you have Chiro there, setting up his drums before the recording of either ‘Prithibi-ta naaki’ or ‘Aamar dokkhin Khola Janlaa’ ; you have one photo each from the field shoot of Arnab Chatterjee’s song ‘cricket’ and Lokkhichhara’s ‘Porashonaay Jolanjoli’; there’s Surojit blowing the clarinet for ‘Aami Daandike Roi naa’ ; and there’s Dibya-da, singing behind a glass painting his hypnotic song ‘Akashe Chaorano Megher Kachakachi / Dyakha jaay tomader baari…’

If I remember it right, there were over 30 hand-painted glass paintings specially created for that song. It was shot at the Indrapuri studios – and the entire video was about shifting focus from the images on the glass painting onto the performer, which was Dibya Mukhopadhyay.

I will tell you more about that, but first let me bring you the memoirs of one of his direct student’s from SRFTI, without whom this blog post might not have been possible. Yes, it’s Tapas Nayak; he is a great well-wisher of my blog, and I eagerly await his comments on the topics I choose every time.

It’s just that this post was special for him as well, not just me.

The same doesn’t stand true for Videogaan.

At least to my knowledge, those videos are well and truly lost. There might be some half-inch VHS copies – but their quality will be suspect. But allow me to try and recollect some moments that I spent with them, so that others can at least know about them.

So when Dibya-da was singing about the ‘badami beral’ – there was actually a badami beral grinning on the glass painting behind which he was lip-syncing; there was a ‘chaai ronga pyancha’ as well; Dibya Mukhopadhyay even tried walking along the (virtual) ‘ajana laal surkir poth’ while singing those lines.

That exercise asked for a large number of takes, because what he was trying to do was much like a rope-trick – walking along a chalk-mark across a pitch dark studio, with multiple directional spots straight on him, while trying to act normal, strumming a guitar all along while facing the camera.

All that while Vivek Banerjee, the cameraperson, was trying to keep the focus shifting between the far-away him and the ‘surkir poth’ on the glass painting right in front of his camera. Dibya-da had to be far enough to make it feel like that he was part of the painting.

Tricky, yes; but Dibya-da did manage somehow; and that video came out really well.

This is now sounding a bit ridiculous even to me, despite my ardent wish to write about it; can’t talk in such detail about music videos that most people who will read this blog have never seen, and will probably never see.

So let me just give some brief pointers, for now. Correct me, my readers, if you were part of those video shoots – because all of these were 25 years back.

Look what I found from the net.

This looks like to me one of those hand-packed cassette covers that I was talking about

in the first part of this post – ones we distributed from the A Mukherjee stall at the book-fair of 1995.

Definitely not machine-packed – this one.

Many of those songs were shot outdoors. If my memory serves me right, ‘Ganga’ and ‘Ghenna Koro’ was shot in Nalban – which was quite new then; ‘Cricket’ was shot in Mohammedan Sporting Ground; ‘Porashonaay Jalanjoli’ in Indrapuri Studio annexe gardens and ‘Prithibi taa naaki’ at New Digha.

Each song video was treated differently – and there was something in each of them to bring out the thematic premise that the song alluded to.

Even after 25 years, after many seasons of afterthoughts, I still have first-hand reasons to believe that each one of them entailed a heady mix of structured innovation and cohesive spontaneity – and that’s what always defined the work of Gautam Chatterjee.

I think Tapas Nayak meant the same when he referred to his ‘methodical madness’; another of his students, Sayandeb, calls it his ability of being ‘vehemently constructive’, while also being ‘wide open to experimentation’, at all times.

Even then, much before ‘Bhoomi’, he used to play multiple instruments.

I also fondly remember some of the Videogaan videos that were shot indoors – like Antara Choudhury’s ‘Elo ki e asomoy’ and Surojit’s ‘Aami daandike roi naa…’

More so since they gave me the opportunity to understand studio lighting and certain other tricks that have helped me in the long run. Antara’s song, for instance, was an exercise on how to turn a limited space into a horizon with staggered depth – the song was shot much like a Bunuel dream sequence (with Antara chasing rather uncontrollable and desperately clacking live swans during the song interludes – a scene that still remains etched in my mind).

Surojit’s song, on the other hand, was my first exposure to Chroma key. If you are from this industry, take a look at that picture above, and you will see the blue backdrop against which it was shot. Yes, back then, Chroma clothes used to be blue, not green. All sorts of things were inserted later onto that background.

Ritika Sahni anchored the show, besides lending her voice to ‘Aamar Dakkhin Khola Janlaa’, which was a studio shoot as well. Her anchor links were also shot against chroma. I specially remember their background, mainly due to its innovative stylization.

We took a large slab of glass and applied glycerin on it, rather lavishly, while staying careful that it shouldn’t affect the transparency of the glass. The glass pane was kept horizontal to the ground, with a slight tilt. Colours were poured slowly from all sides, and allowed to freely mix over the glass and glycerin. This entire set up was hard-lighted from below, and the camera captured it from the top angle- directly above.

The results were magical. All those primary colours were coming together and jostling for attention, while talking to each other to create myriad random hues. Nobody could predict how those colours would interact with each other. No one knew what the final outcome would be. It was all a spontaneous, free-mix of diversity, but within controlled conditions, under the ambit of the strict guidance of Gautam-da.

That’s how Gautam Chatterjee created his music as well.

Anyone who has ever been part of one of his song-composition sessions would agree with me on that, including his students from SRFTI .

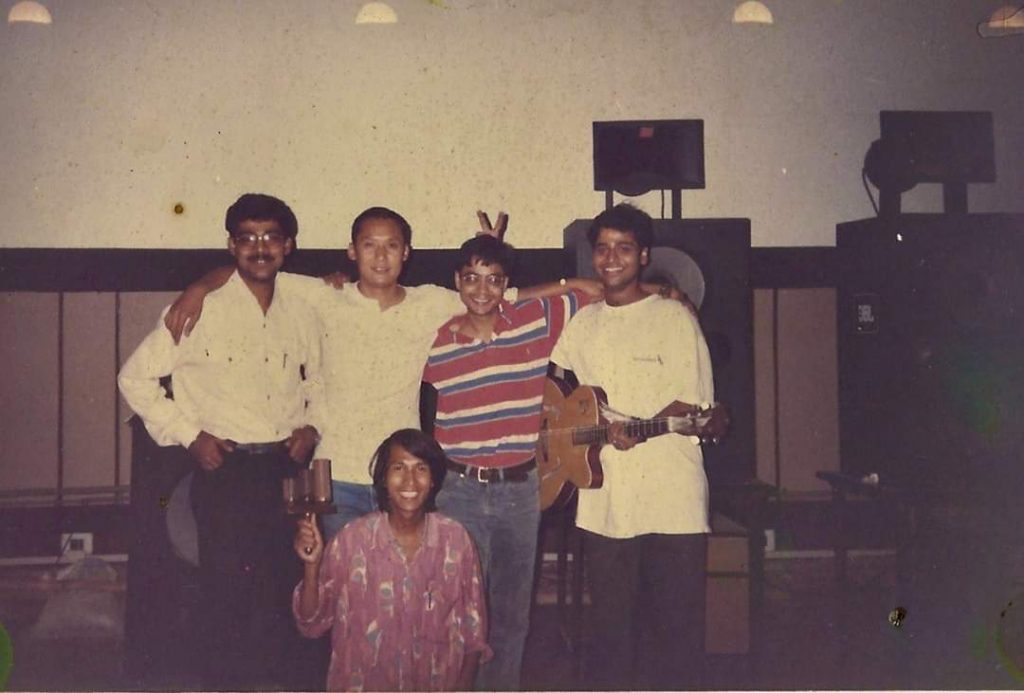

SRFTI re- recording studio. Standing from left Rupesh Kumar, Anirudh Garbyal, Late Aseem Seth, Sudeep Chakravarty, sitting Julius L. Basaiawmoit.

Taken on one of the practice sessions for a fund raiser concert in SRFTI campus in 1998 .

Picture courtesy Rupesh Kumar.

That picture above was taken during the rehearsals of a fundraising concert held at SRFTI – during the time when Gautam-da was a teacher there. My next two back to back memoirs reveal a barrage of unknown facts about what went behind the scenes in that concert.

Hope you enjoy them.

When I met him, I requested Sudeep to play a little something on his Mohan Veena in remembrance of Gautam-da. I requested for ‘Kotha Diyaa Bondhu’ – since I have a lot of fond memories around that song, including a ‘situation’ when I had to sing its harmony section at the Jadavpur University Union room, with Gautam-da. People who are aware of my singing voice will be shocked, I know – but he was like that. He was probably the only person who ever thought I can sing.

But Sudeep insisted on ‘telephone’; and he has already told you why.

Now for the recollections of Julius, another excellent musician and sound artist from the second batch of SRFTI. You have already seen his picture up there, holding what seems like a percussion instrument, during that rehearsal shot.

Julius found this invitation card of that show, from twenty years back, in his closet.

This was probably the first and the last time Chandrabindoo shared the stage with Gautam-da. I am not too sure. Their relationship, however, was far more deep-rooted. The fact that one of their key band members Chandril Bhattacharya was a first batch direction student of SRFTI might have further cemented this relationship.

About five years back, when I was planning to write a bangla book on Gautam-da, I interviewed Anindya Chatterjee and he shared a lot of fond memories with me. That book never happened – since I started feeling only a qualified musician should write such a book. I was, and I still am, just a ‘ghodaar dim.’

For now I really think this post will remain incomplete without a brief mention of Amitabh Chakraborty, director of the art-house classic Kaal Abhirati. This maverick FTII editing maestro was a close friend of Gautam-da. He edited Videogaan.

Those couple of months spent with him in the ice-cold confines of Focus Studios will forever be my lighthouse on editing techniques.

Amitabh is a master craftsman – intent on giving every frame its due position. I remember his instructions vividly – ‘give two frames from the left’ he would say… and then say, ‘nay, I think it should be 4 frames from the right’, and then, ‘can you just add two more frames to the fifth shot…” – and finally, “Naah, hochche naa, let’s take the whole thing from the top again…”

Well he was a film editor.

And if you have ever known what linear video editing was like in those days, then you will realize the challenge of doing all of that using a RM 250 remote. Those editing set ups were not designed to behave like a Steinbeck; every new insert meant a fresh tape, and every dissolve meant going a generation down.

But it was done, meticulously. It was pure abstraction, those edit sessions.

Talking of abstraction – let me tell you my reader, that I have kept the dessert for the end. Just to test your patience, if I am allowed to do so, at times.

I now bring you Aparaj Sharma from Assam, first batch SRFTI, with his poem on the ‘Gautam-da’ mystique. Curiously, like all abstract works of art, this too is an open window. You can own it the way you want to.

But yes, if you knew Gautam-da, this will start owning you.

Let me mention here, that this is the second and concluding part of the therewillbetime tribute post on Gautam Chatterjee. Many thanks to all the first and second batch students who participated in this. I am sure this opened up a floodgate of memories.

In case you have come here first, you might consider visiting our first part.

That’s all, as of now.

I will find an opportunity to write about ‘Nagmoti’, talking to its key team-members and performers – but I don’t know when that will happen. For that, I need to go to Kolkata.

As of now, I really needed this post, like I said, to move on.

I am again at that critical juncture of my life, when this need to rediscover myself has become a dire necessity. I am feeling like what Tapas said about the sailor of the seven seas and his interns; here I am, standing by the shores of a limitless ocean once again, waiting for the master sailor to point out to the boats that I could take.

It will be my journey, yes.

But now, I think it will be with your blessings Gautam-da, always my master sailor.

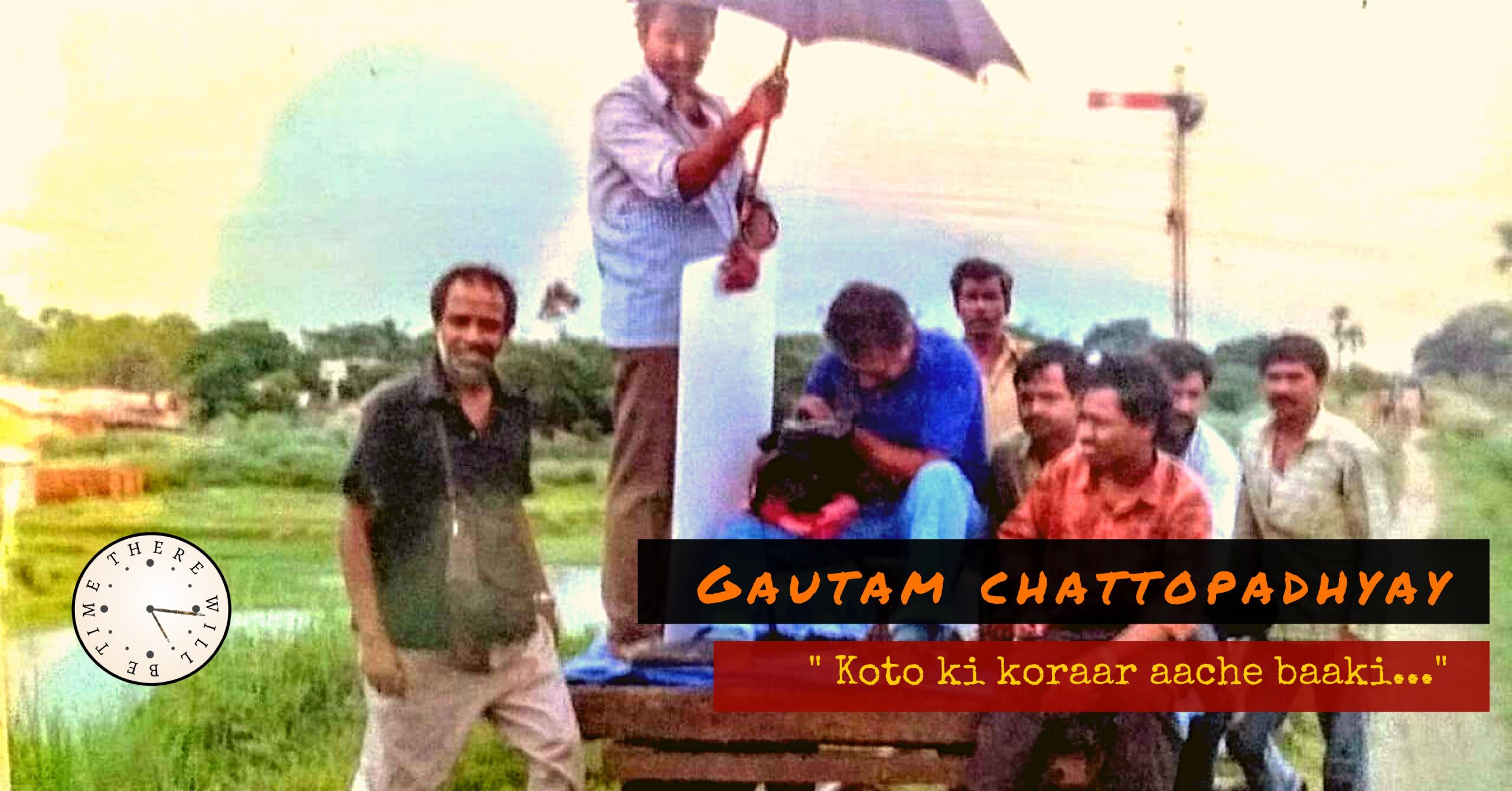

From the sets of ‘Nagmoti’, Gautam Chatterjee’s National award winning debut feature.

Someday, I will write about it – but I have to watch the film first.

Thanks for the pictures again, Minoti Chatterjee.

Excellent post…

Thanks a lot Gautam.

Excellent writeup. Never knew Putu (Minoti) had kept those few invaluable pictures with her. The contributions from the other students have strengthened the blog to a large extent. Wonderful !

Thanks a lot Vivek-da. In fact they are the ones who pushed me into this, and I am grateful to them for that.

Will earnestly look forward to a write-up on Nagmoti. In case if I am of any help, please feel free to involve me. Nagmoti was the film when both, Gautam and I began our journey together in the film arena

Haan Vivekda. I will when I come to Kolkata, that might take some time – but I definitely will.

Excellent write-up, while reading it I felt like, as if I was present at all the occasions that you mentioned. I could imagine the pains? and sincere hardwork that you all had to put to get the desired output.. those days were hard but those days had the passion which was raw and genuine.

Thank you for taking us down memory lane.

Thanks a lot for reading Chandra Shekhar.

Fascinating

Thanks Nishi.

Loved reading through the students’ precious memories!

This is beautifully written, Rana. Thankyou!

Thanks a lot boudi. That’s one chapter about which I always wanted to write, being his student himself. And you do know he didn’t like it when I didn’t join SRFTI.

I loved Sudeep’s rendition of ‘Telephone’ on mohanveena and Aparaj’s poem.

Will tell them that, in case they don’t read this. Sudeep stays just a few blocks away.

That Bochhor Kuri album cover is my contribution to the Internet. Back in 1996-97, I started building a Moheener Ghora webpage and scanned all their covers . I told about this to Gautam da but unfortunately he passed away before I could show him my work. The website no longer exists but these album covers and some song booklets I uploaded still survive in the Internet.

That’s lovely. If you find some time please assemble them at one place again – it would be lovely. It’s encouraging to know that you were building web pages in 96-97, when we didn’t even have access to personal computers. It would be fascinating to take a look at those song booklets you mentioned, especially that of ‘Abar Bochor Kuri Pore’. Thanks for responding again.