In retrospect, I have done quite a lot of useful things with my rudderless self – most of which I don’t even care to remember now. Having said that, the couple of years I spent with stage lighting have remained firmly embedded in my head, as a sweet spot.

I still love the lights, and not just the limelight.

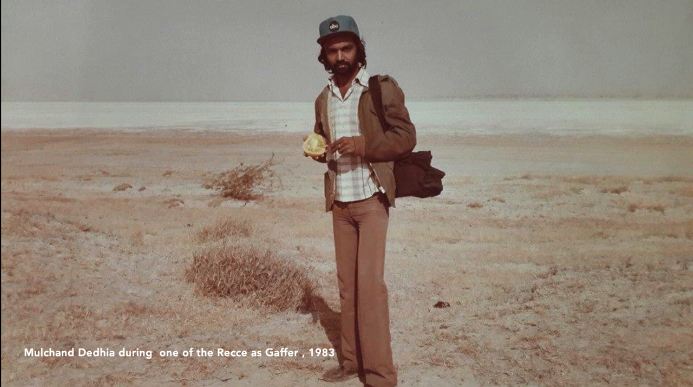

So when my well-wisher cinematographer Hemant Chaturvedi pointed me towards the undoubted pioneer of film lighting in India – the internationally coveted Gaffer ‘Mulchand Dedhia’ – I jumped at the opportunity.

But first let me tell you what the designation ‘Gaffer’ means. I have a nagging doubt that (like me) you might have never heard the term; or even if you have, might not know what it entails.

So here’s a definition I picked up from Masterclass.

“The gaffer is the chief lighting technician on a set and is head of the electrical department. The gaffer’s job is to run a team of lighting technicians to execute the lighting plan for a production.”

In India, the use of a proper gaffer still remains limited to a select few directors. It’s more common with better organized foreign crews, so most of Mulchand’s work has been with them. We will come back to that, but if you are in a hurry, you can always go to Mulchand’s IMDB page and check out his rather impressive list of films.

When he started in the eighties, the concept of a dedicated Gaffer was unheard of in our film industry. The fact that this has changed a bit is largely thanks to his dedication, and four decades of unwavering commitment. But yes, despite all his stellar achievements, Mulchand still comes across as a humble man and a habitual learner.

A doggedly self-trained professional, he learnt everything at his job, mostly by watching, and without any institutional training. Mulchand has picked up everything he knows from life.

And what a life it has been.

An incredible rags to riches story, laced with pure passion and love for cinema.

What he didn’t mention here is that his first key international project was not ‘Heat and Dust’ but a multi-starrer film called ‘Sea Wolves’ – featuring Hollywood biggies like Gregory Peck, David Niven and Roger Moore.

Its crew came to India in 1978 to check out equipments. While they ended up bringing almost all lights and gears from abroad, the generator was built in Rajkamal Studios – by the British Gaffer, his British Generator Operator and their Indian assistant – Mulchand.

That’s was India’s first ever home-made silent generator – and the British Gaffer John Fenner became Mulchand’s inspiration. As an (uncredited) Generator Operator to ‘Sea Wolves’, he observed Fenner closely. That was the first time he thought – yes, I could do this.

Heat and Dust followed soon.

Question remains – did all this experience in working with foreign crews give him a stronger foothold in the Mumbai Film Industry? They must have welcomed his new knowledge-base, professional and efficient style of working with open arms – right?

I somewhat feel you already know the answer to this rhetorical question.

Mulchand has had an awe-inspiring career with truckloads of work, with major foreign films – spanning across four decades. Writing one blog post on him is tough . Hence, primarily to make my own job easier, I asked him about his most challenging assignments.

He skirted the question. He says he had always taken up every project as a challenge, be it a one week or four weeks schedule.

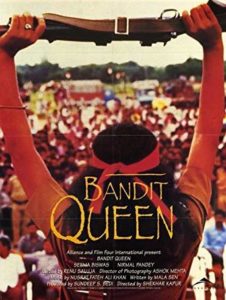

Having said that, there are a few projects that have remained etched in his memory due to their precarious shooting conditions and tough deadlines. That includes projects like Shekhar Kapoor’s Bandit Queen (1994) –shot deep inside the ravines of Chambal.

On one hand, there were films like ‘Bandit Queen’ (94) and ‘Electric Moon’ (92) and ‘The Jungle Book’ (94) – placed deep inside the badlands of back-of-beyond India; on the other hand, there were films like Meera Nair’s ‘Salaam Bombay’ or Sudhir Mishra’s ‘Dharaavi’ – placed entirely in the urban slums of Mumbai, with its own repertoire of unique lighting challenges, and their impromptu solutions.

Soon enough, thanks to his insatiable passion for cinema, Mulchand found himself importing the latest lights and creating his own clamps and rigging equipment. Those were the times when even dollies were hired from abroad – and that too only for big-budget films. He started making his own scaffolding and grips for lighting. Besides gaffer, he also worked as a grip.

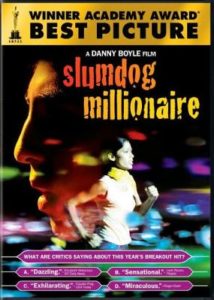

So by the time Danny Boyle’s team approached him for ‘Slumdog Millionaire’, he was fully prepared to meet any lighting challenges head on.

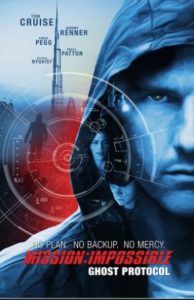

Personally, I am a big fan of the ‘Mission Impossible’ franchise, and I am yet to develop a friendship with anyone who isn’t. So my next obvious question to Mulchand was about Mission Impossible: Ghost Protocol (2011) – where the entire climax was shot in Mumbai.

It wasn’t a very long sequence, but within that short span, I saw so many crowded locations in Mumbai in an entirely new light; almost like I was not being able to recognize Mumbai. I particularly loved the chase sequence though the streets of Bora Bazaar.

Now let’s go back a few years.

At the turn of the millennium, Lagaan and Dil Chahta Hai were two cult-classics that transformed the way commercial films were made and perceived in India. I do remember watching them multiple times in big screen – both kept me mesmerized.

Besides Aamir Khan, Mulchand was the common factor in both of them.

Anil Mehta was the DP for Lagaan, so in his long ISC: Conversations interview with Mulchand, they went on and on about that film – including interesting anecdotes about cabling and the use of Chinese lanterns to light up the song ‘Radha kaise naa Jale’ etc.

I would propose all serious students and enthusiasts of cinema lighting to go through that interview cover to cover. It’s a real study in contrast. While Lagaan was mostly outdoors, Dil Chahta Hai had extensive indoors sequences. If Mulchand didn’t tell me that it was all sets and not real locations I wouldn’t have realized it – although I have lost count of how many times I have seen DCH in the last two decades. Mulchand designed special lights for those sets, neatly planned and integrated in the film’s production design.

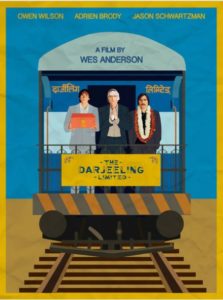

See that interview. For now, here, let me bring you another interesting challenge – a lesser known film called ‘Darjeeling Limited’ (2007) – shot inside a real moving train. Not a set – but a real train, travelling across landscapes. The idiosyncrasies of it’s Director Wes Anderson added on to the formidable challenges of achieving something that complex.

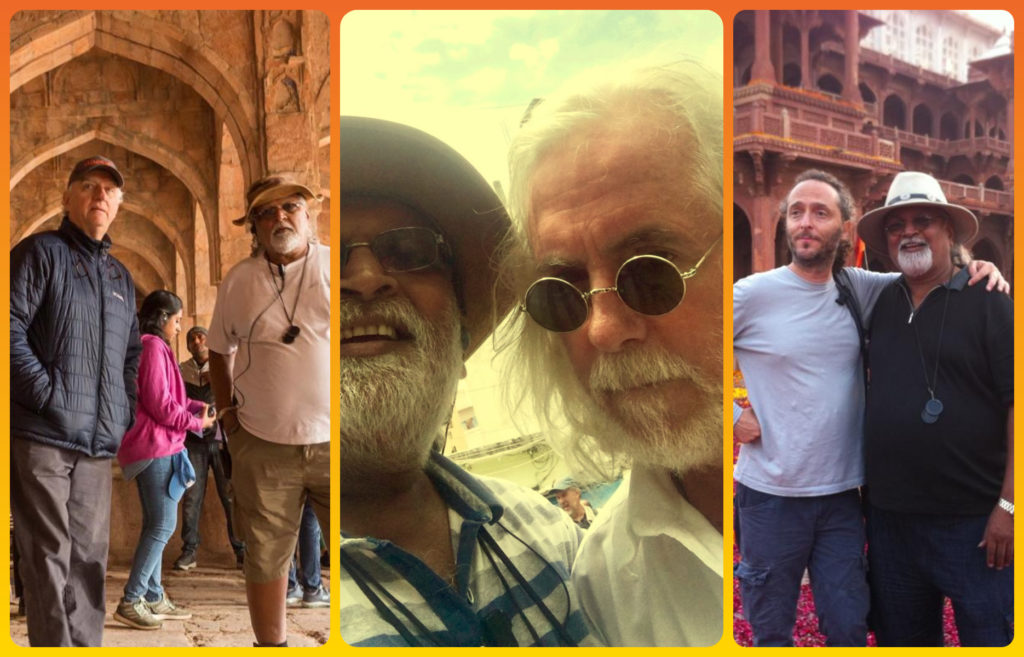

Mulchand also thrives on the relationships he has built with globally renowned Cinematographers – over time. One particular example is that of Giles Nuttgens – with whom he worked in the Deepa Mehta trilogy Fire, Earth and Water. He has also worked with undisputed masters of the craft like Emmanuel Lubezki, Dion Beebe, Robert Richardson and Declan Quinn – just to name a few.

In all this exposure to international masters of the cinematic image, there’s one aspect that stands out for Mulchand. Every time they come, they want to do something different – never repeating themselves. That keeps the lighting crew, in this case Mulchand and his team, always on their toes – and ready to experiment.

The job of gaffer has never been easy. It’s become even more complicated with time.

To start with, you need to understand a wide range of requirements – that of the cameraman, director and the script; you have to understand the technology and the aesthetics of a camera – usage of lens, depth of field, colour temperature, exposure and all that. You will also need to know what light head will be most suitable for which location and what moods will it convey? Understanding the photo-metrics of lighting has become even more complex since now there are over 10000 varieties of lighting heads – from LEDs, to Tungsten, to a vast variety of HMI; you also need to have a firm knowledge of load distribution and cabling on the sets – for a trouble free session of shoots.

Mulchand also mentioned how the sound guy should also be involved. He explained how there have been situations when he had to place a high-intensity HMI really close to the sets – and how that could create ‘humming’ issues for sync-sound recording. This mention put a smile into my face – since sound has been my long term passion. And I am quite sure this is where my friend Tapas Nayak will also be smiling.

It’s all about collaboration and teamwork; and an obstinate urge to keep learning, which only comes with an undiluted love for cinema. At the end of it all, Mulchand did manage to make a sizable difference in the way things were done in the Indian Film industry. But that’s because he chose to be uncompromising with his quality of work.

If you have seen these three films, you will know what I mean.

Mulchand is taking it a bit easy now. At the most he attempts two films in a year.

Over the years, he has managed to create a pool of gaffers in Mumbai – including his own daughter Hetal Dedhia. Acclaimed as the first ever female gaffer in India – Hetal is doing significant work. Here’s a verve article on her.

But yes, when the likes of Mira Nair pick up a complex project like the BBC Mini Series ‘A Suitable Boy’ (2020) – she still ropes in Mulchand in person. Might be because they have worked together for 34 years – in all films she has shot in the Indian subcontinent.

Mulchand has not just transformed the diction of lighting in India – he has kept changing himself to be up to date with the best in the global industry. He kept on raising the bar, of the kind of equipment that we use, and the way we work.

That’s what kept him going all these years. It still does.

That’s solid life-advice, if I might say so.

I have seen quite a lot of people trying to match up to the expectations of others – and thereon failing to reach anywhere at all. It’s not easy understanding what you really want to do, and be the best in that field, even if it doesn’t feel lucrative or romantic enough at the onset. It will pay off eventually.

On that note, I close this post.

It’s been a long time since I came up with a blog. Even this interview was taken a couple of months back, but due to a string of personal tragedies and other sentimental engagements – I couldn’t focus on blogging.

From here on, I would like to rectify that. Let’s see.

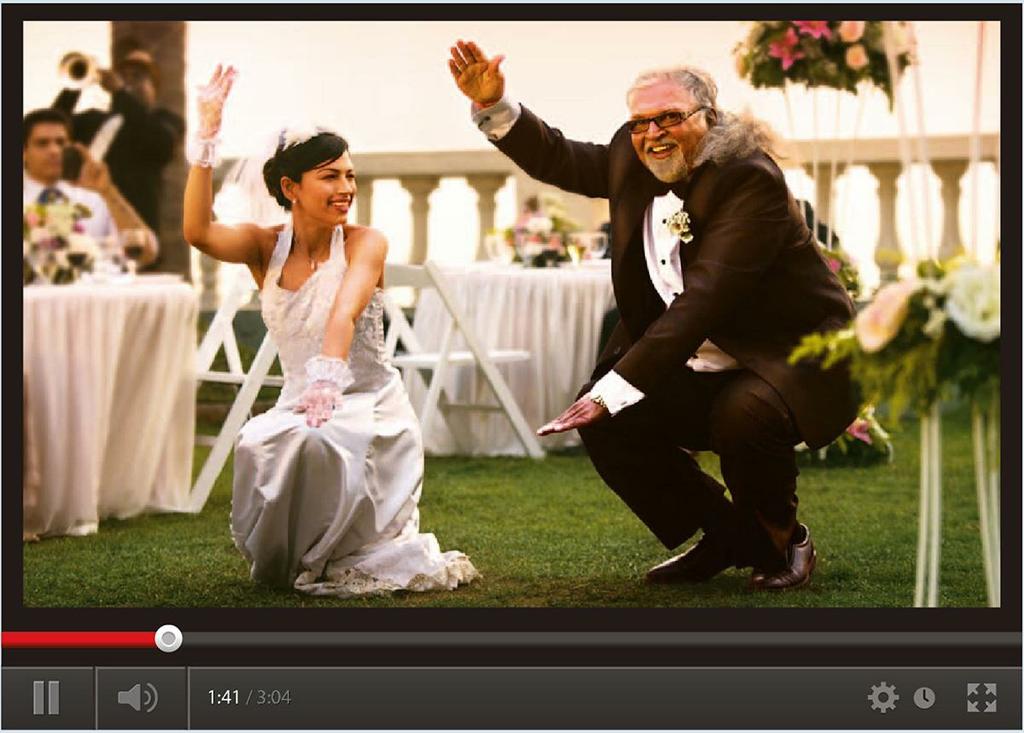

Here’s a glimpse from a Vodaphone commercial.

Thoroughly researched and articulated. Informative yet written in such a manner that it held my attention through and through. And by the time i was done, left me wanting for more

So fascinating… A delightful read…

I got caught up in the narrative, so effortlessly it flows. Very interesting information, too .

Very nice Anirban Sir 🙂

Well researched and articulated. Enjoyed the read.

Perhaps the most engrossing piece of ‘therewillbe time’ great insight. Umesh Aggarwal