The story of Hitendra Ghosh is the saga of walking willingly into a maze of amazement.

His insatiable quest for meaning partnered with his indomitable will to experiment. It didn’t take any time for his skills to be noticed, recognized, and efficiently used across the spectrum. Be it the multi-layered aesthetics of ‘art’ cinema, or the heightened emotions of ‘pop’ cinema – he has heard it all, and mixed it all.

Even while Hiten was still a student at the Film and Television institute if India, he had this ability to stand out in the crowd. Like he already said in the part 1 of this blog, he wasn’t jobless for even a single day. That’s probably because he loved and respected his work, which reflected in his attitude.

The fact that his student project had Smita Patil in the lead also played a distinctive role. Not for Hiten, but for Smita.

Those few years after FTII were extremely productive times for Hiten – with loads of good work coming in.

That was the time when Indian New wave film-makers were making their debut films – working beyond the traditional formula flicks that characterised Hindi films. That was also the time when the angry young man arrived and became mainstream. Life got complex with thousands of young Indians opting for ultra-left revolutionary routes and the government declaring emergency and the opposition leading nationwide protest rallies – and what not.

The 70’s was a tough time to live. And every tough time to live has always been a good time to make meaningful cinema.

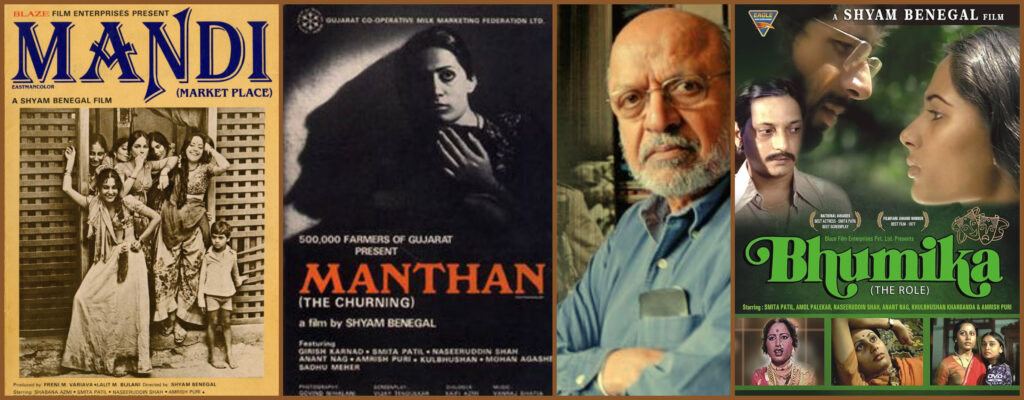

I couldn’t help but asking him about his long-standing partnership with Shyam Benegal. His initial films from those times have always intrigued and inspired me – along with Adoor, Aravindan, Govind Nihalani and to some extent, Gautam Ghose and Aparna Sen.

More recently, I found Shyam Benegal to be a very ‘amicable’ speaker when we interviewed him for Rahman Music Sheets – crystal clear and specific in his opinion.

You can check the interview here if you want to.

So how is it like working with Shyam Benegal?

I was glad that Hiten himself broached the topic of Satyajit Ray. I would have come to him a little later. If I list down the reasons why I came to Hitendra Ghosh for a blog-post, the fact that he is one of the last surviving technicians to have worked with Ray would definitely be somewhere at the top of that list.

We will come to that later. First, yet another unexpected decision from Hitendra Ghosh. Yet another road less taken.

During the late 70’s and early 80’s – Hiten was picking up one project after another, as an overall ‘sound’ technician. He was getting good films – with off-the-beat directors like Kalpana Lajmi, Girsh Karnad. He did ‘Utsav’. He did ‘36 Chowringhee Lane’ with Aparna Sen. Talking of commercial films, he did the sound of ‘Arjun’ with Rahul Rawail, and ‘Saaransh’ with Mahesh Bhatt. All of that and more.

By Hiten’s own admission, ‘Those were great times!’

But then, while at the height of his demand as an established overall Sound person, he decided to focus on one specific aspect of ‘Sound’ in cinema – which was re-recording and mixing.

He had his reasons, and I do resonate with his logic.

The re-recording and mixing work Hitendra Ghosh used to get after joining Rajkamal studios were mainly commercial films. But he still got off-beat films – some of them came from Kolkata. Tapan Sinha used to come, and Tarun Majumdar.

Commercially hit Bangla films too; he did films like ‘Gurudakkhina’ with Anjan Choudhury.

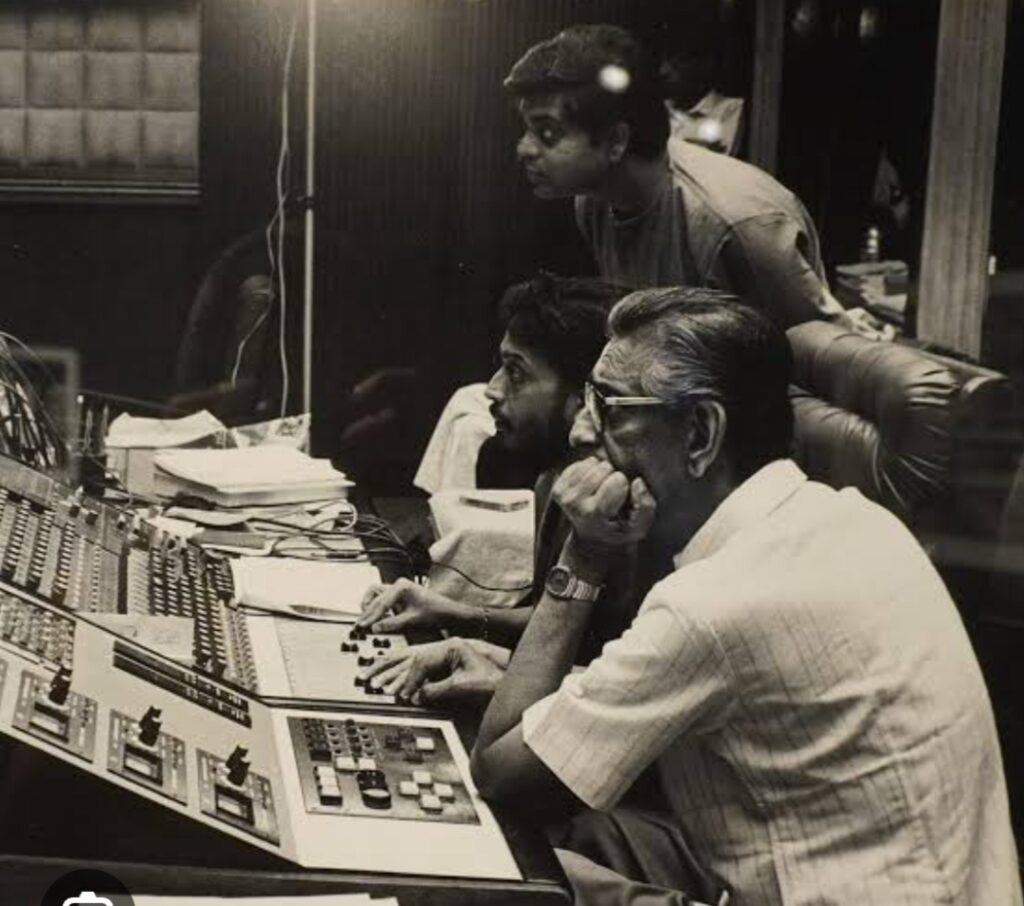

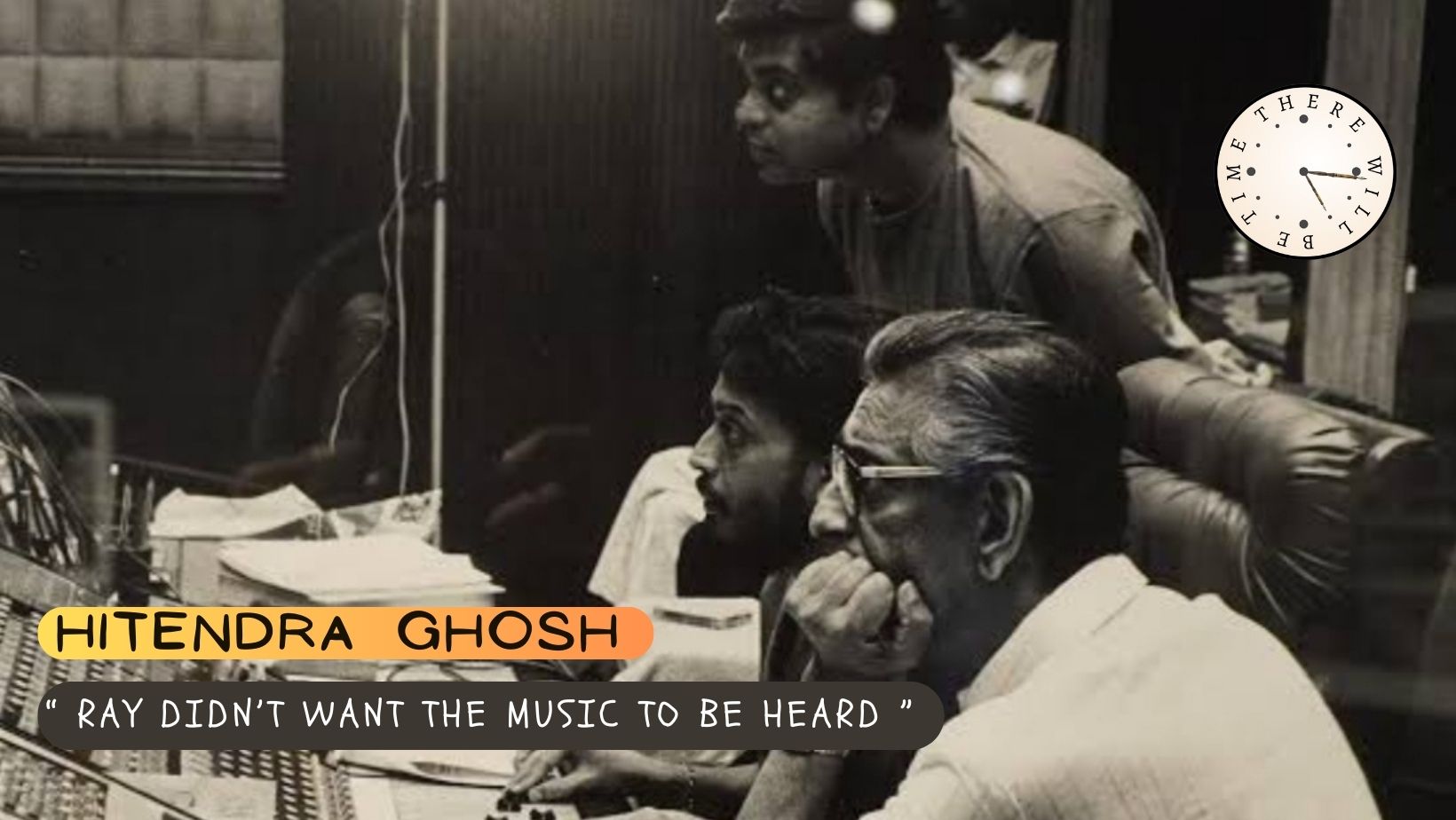

Satyajit Ray, of course, was the icing in the cake as far as Bangla films are concerned. More so because of Hiten’s Shantiniketan connection with Ray – through his parents.

Hiten has a wonderful anecdote to share about his first experience of working with Ray.

Picture courtesy for the above image goes to Nimai Ghosh.

Our conversation continued – around directors that are keen on good sound. Although Hiten was initially reluctant to take names – he loosened up a bit when talking about Mukul Anand. Hiten believes Mukul Anand was one of those directors that had an ear for sound.

When I asked him about today – his top pick was Ashutosh Gowarikar. Hiten says Ashutosh is very particular about sound. To some extent even Subhash Ghai, but his is more about music, while Ashutosh is particular about all the aspects of sound.

He shared what happened during Jodha Akbar.

Ever since I started watching films on big-screen, I always used to wonder who is this guy Mangesh Desai? How come he is there in every film, and what does he do?

Directors direct, actors act, singers sing, someone does the camera, sound, music – so what the heck does this re-mixing, re-recording guy do?

Even after I entered the industry, since my domain has never been fiction, this confusion remained. I did ask some fiction people, but perhaps not the right ones – since I never got a satisfactory answer.

I had to clear this confusion with Hiten Ghosh.

My time with Hiten-da was coming to an end.

If you ask me, I would have stayed a few more hours to listen to all his stories – but he was looking visibly tired.

Which also reminded me of the ‘machine’ he is carrying inside his chest for more than two decades now, something that is more complex than a ‘pacemaker’. In his own words, ‘Pacemaker keeps pace for hearts that are still functioning. This one is for dead hearts.’

With the turn of the century, Hiten had a massive heart attack – and since then, this machine sends an electric pulse to his heart to keep it pulsating. Forgive the wordplay, but this means his heart does not beat normally any more, it is being kept functional artificially.

Yet there is rarely a day he misses work. This interview also happened between two of his recording sessions, in studio.

I don’t know what that says about his tenacity towards life and work; you tell me.

To round up the discussion, I asked him to mention five films that students of cinema should see, from the sound perspective; not necessarily his own films.

I came out of Empire Studios with overwhelming feelings.

All my life as a media-person and a writer – I have consciously avoided iconic cultural figures. Might be my own fear to connect, or maybe I felt intimidated by what I felt to be their towering presence.

But here, I very much wonder, whom did I just meet?

Without doubt this humble, welcoming, ever-smiling gentleman in there have played a seminal role in the history of Indian cinema for fifty years now – as an undisputed maestro in his craft; the quintessential silent worker, literally hand-mixing a plethora of films – guiding them gently towards their destination.

Without realizing, I have just met an icon, also an everyman.

People like Hitendra Ghosh brings back my faith in the power of passion. He stands tall, uncompromising as always, and ready for the next trial. Incessantly vouching for the right mix of emotions. Forever standing with and for cinema.

Keep taking up challenges Hiten-da. One film at a time. Hat’s off.

Be First to Comment