To be honest, I never had the opportunity to work directly under Nilendu-da.

During my early years in the Delhi News TV circuit, I might have seen his signature gallis-mounted frame a couple of times during my not so frequent visits to the Moving Pictures office at Jangpura, where I used to go meet my friend Laura Krishnamurthy.

I remember him as the ambiguous big-boss, and since I was forever in lookout for a job, I felt shy approaching him directly. Later on, during my stint in India Today TV, he was so high up in the ladder that even though I worked in the same department, he would have required the Hubble telescope to spot me.

But something strange did happen there.

Maybe because I was in the team of one of his closest associates Sujay, whenever I went anywhere near Nilendu Sen’s expansive cubicle – he always welcomed me with a warm smile. This encouraged me to spend time with him, whenever that was available, and the ice started melting.

That was over ten years back, and we are still very much in touch.

I have neither the skills nor the audacity to talk about his achievements. Perhaps it would suffice to say that I have always admired him for his keen understanding and deep knowledge of a variety of things, and his ability to present them simply enough for the benefit of people with average intellect, like me.

Above everything else, Nilendu Sen is a great storyteller, in every sense.

So when I got an opportunity to finally pin him down, and convinced him to share his own ‘story’ with me, attempting to figure out how he does what he does – I knew I was in for a sumptuous treat.

What follows is an excerpt from a long chat we had, over a Chinese app that I can’t name in these complicated times. The nation doesn’t need to know that.

Nilendu isn’t a ‘trained’ TV producer, or writer, in the (now) conventional sense.

When he started working, there wasn’t much opportunity to academically learn TV, since there wasn’t much of a TV around. His skills should better be termed as ‘life-skills’, derived from his enormously curious approach towards life – and everything that makes it worth living.

During our ‘adda’ sessions, I have always been intrigued with his ability to appreciate and critically analyze stuff, in particular music – much like a seasoned musician. He picks up elements from his repertoire, co-relates it in a manner that I never thought was possible, and presents his arguments which are often irrefutable.

So I started our blog-chat with music – and he told me how much of this came from his grandmother, who was class five pass, but would actually spar with people who held Doctorates in literature and classical music.

I so agree with Nilendu on this. The concept of morality keeps shifting with the intended audience of any work of art – which is all the more true in the area of performance music.

Like Nilendu explained, what they created in terms of content, and how they sang it often depended heavily on who they sang it for. If it’s devoted to a person in flesh and blood, it can’t be similar to the way you would sing it for your intended almighty.

And yes, I also agree, all those things that you learn by chance, or simply by being at the right place at the right time – later on work for you when you are working in a visual medium or you are writing or you are doing whatever else creative. Like he said – all these assimilation that you peel off your skin of memories helps you create your narratives.

That’s a bit super-heavy, methinks; calls for another story.

Those evenings seem so much like from another era, doesn’t it?

Life used to be much slower back then; we had the patience to wait for a whole year for the next much coveted EP of our favourite singer – mostly with just two songs, one side each. The problem of plenty that’s hounding us today wasn’t there, and lots of thought went behind each song that entered the public domain.

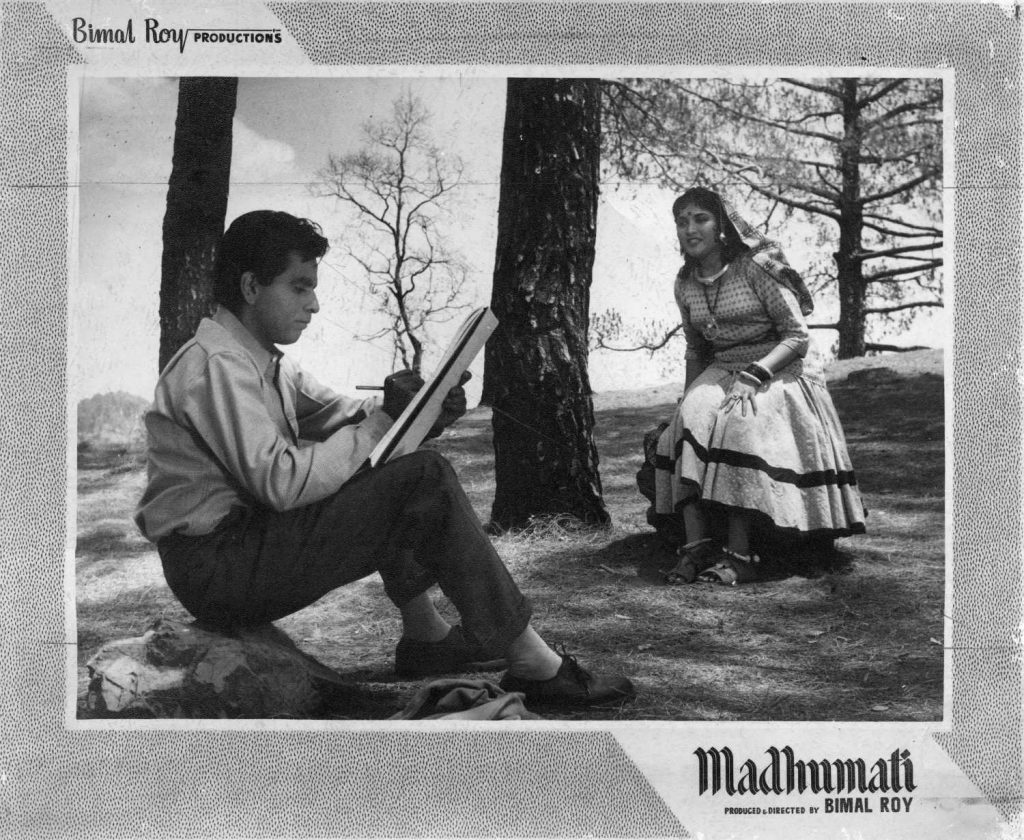

Nilendu told me those locations were not too far from where their mountain bungalow, and he often went visiting them.

This is not to say that all was hunky-dory back then, and things are all topsy-turvy now. But yes, learning was tougher, and access was limited. Just how much this ease of access to information had lead to actual ‘learning’ is a separate discussion, we can have that later, in some other platform.

For now, let’s focus on how Nilendu learnt his ropes, and used them to knot his ideas – as and when he had the opportunity.

Nilendu’s experiences in Broadcast media spans more than three decades, with over 30,000 hours of programming. I won’t give his resume here. You want to know more, you can always go see his you-tube channel. I often do, to steal ideas.

More recently, he wrote a novel, Sonaar Gaon, based on a social effort by commercial sex workers of Kolkata. I remember him telling me that it was originally a screenplay, which he later turned into a novel.

But it’s not the variety or scale of his work that pushed me to go talk to him.

It’s his ability to hold on to a certain quality index that he had set for himself quite early in his life that interests me more. Lots of us dream big when we come to this media, but somehow lose it midway. Not Nilendu.

I wanted to feature him because I believe he is a true pioneer; one of those unsung TV producers who created magnificent edifices out of nothing, and set standards across programming genres.

He had no norms to follow, so what he did became the norm.

Portrait of the Director, and then Biographies, set the parameters for much of the long-format Cinema programming on TV that we get to see; Subah Savere was one of India’s first hugely successful breakfast TV shows; Mukti Gatha, the official documentary on the occasion of India’s 50th Independence Day defines how to make a period film without much of archive footage; and so on, and on.

I believe, if someone writes a people’s history of Indian television, he will have to dedicate at least one entire chapter on the exploits of Nilendu Sen.

That’s not the only thing Nilendu said about cinema.

In fact, that was among the last things he said on cinema. We spoke for over two hours on various topics – and a lion’s share of it was about his romancing the big-screen, and inserting that amour in his TV programming. I will bring that to you, but in part two of this post. This one was more about music. That will cover cinema.

Like many of us, he started with theater while in college, and moved on to TV. But what did he do (or get) that gave him that ‘extra’ edge? What was it that makes him ‘special’??

His story is a success story for sure, but how??

I think I should give Nilendu Sen, one of the best storytellers I know, to tell that story himself, without paraphrasing. But even for a long format blog, this is way too long, so I think I should call it a day as of now.

You have to wait, just a couple more days, for part two; I promise to make it worth your while.

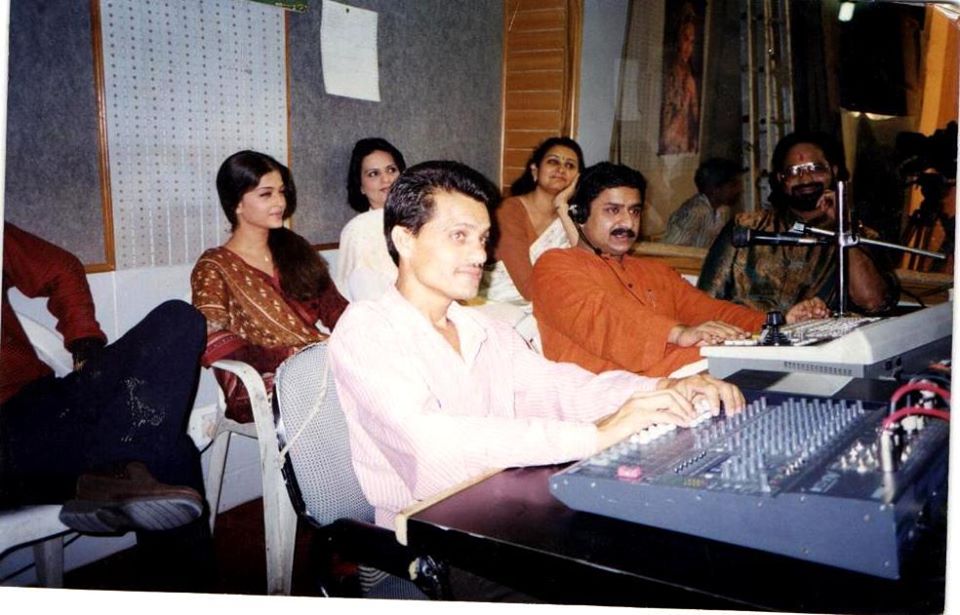

One could also spot a newcomer Aishwarya Rai and the timeless Pt. Viswamohan Bhatt in the backdrop.

Despite knowing him for more than two decades… today I realize how little I knew of him. Thanks for this insight.

Which makes me wonder, how little I know you Umeshji, despite our more than two decades, from the times of Heads and Tails.

Excellent… Waiting for part 2

Definitely by this weekend. Working towards it.

Very interesting and refreshing dear Anirban,in this Covid atmosphere.

Looking forward to your next blog.

Stay safe.

Thanks Prosenjit bhaai. Need to celebrate things we cherish. If we don’t, who will??

Fascinating! Looking forward to Part 2!

Yes, I am looking forward to write it too. And on your documentary on cinematographers, once that is done.

Aishwarya wasn’t exactly a kid then but yes, she had recently delivered her first megahit. Hum Dil De Chukey Sanam. Subhash Ghai launched his film, Taal, on Subah Savere and therefore those guys were there. There is a hilarious story with Aish and Pt. Vishwa Mohan Bhatt. https://www.facebook.com/search/posts/?q=Aishwarya%20Rai%20and%20Vishwa%20Mohan%20Bhatt&epa=SERP_TAB

Very well-written Anirban, very interesting!

Wow. You made my day. Please continue reading my posts.

Very well-written, very interesting!

Nilendu is an absolutely fantastic writer, director and documentary filmmaker. It was my privilege to have worked with him. Thanks for the very insightful article, Anirban.

Thanks for reading Sudarshan.

Dost.I love my Nilendu and do not forget his greatest weapon..His Quick Wits.!!

How can I ever forget that …and many thanks for reading Arvind.

The devotional piety of Pratima Bandopadhyay..

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FXH5yd6TZxI

The husky demand of the lover. Angurbala

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h6pqLfUj8Cc