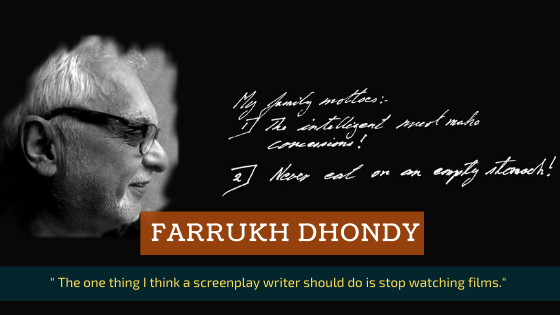

It’s not every day that you get to interview someone like Farrukh Dhondy.

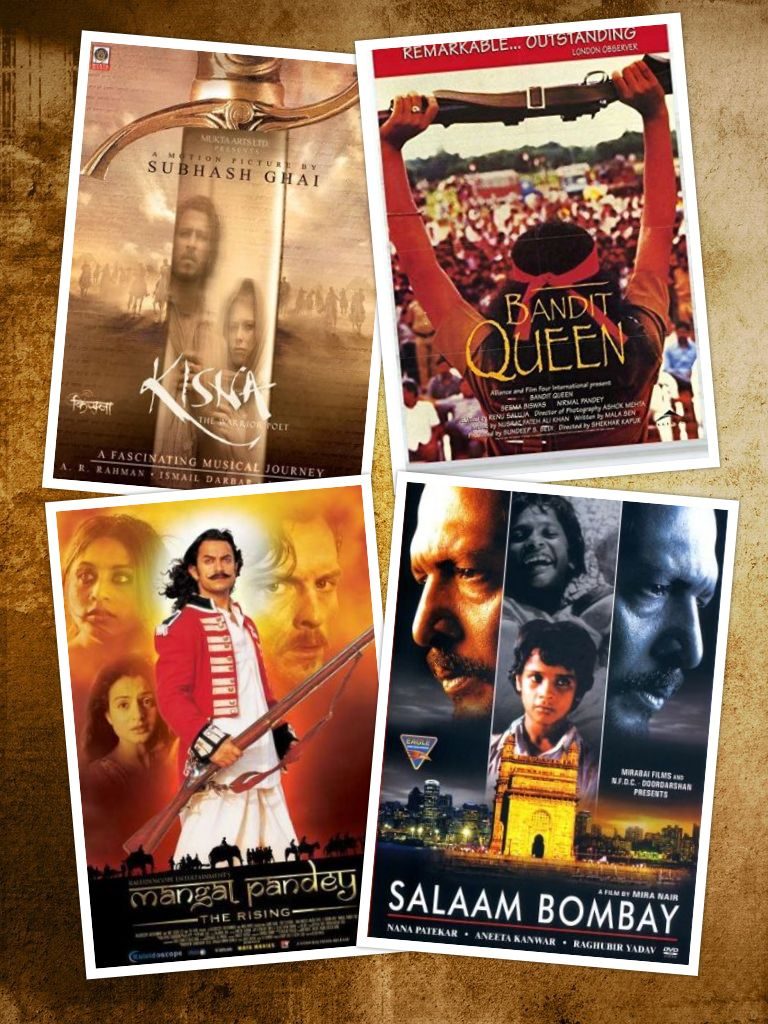

All I can say, films he has worked in have been films that inspired my very early thoughts about choosing a career in screenwriting. I remember breaking down the ravine sequences of ‘Bandit Queen’ when I was barely 20 something old – to learn editing and sequence pacing. I remember spending hours absorbing again and again the ambient sound of the road sequences of ‘Salaam Bombay’ – and trying to follow that itinerant style with hand-held cameras for my news-feature edits in my first job with city cable – I remember even now the incredulous look in the eyes of my boss with a tinge of inexplicable satisfaction.

Anyways, there are some days when you need to just shut up and listen; today is one such day. I will just give a brief intro of Farrukh for those readers who might not fully know the expanse of his work. I have copy-pasted an intro from Harper Collins – you can always Google him if you want to know more.

Farrukh Dhondy is a screenwriter, playwright and bestselling novelist. Born in Pune, India, in 1944 he went to school and college in Pune and then to Pembroke College, Cambridge. He graduated in 1967 having read Natural Sciences and English. He went on to do a thesis on Rudyard Kipling at Leicester University and then taught in London schools. He began his writing career while earning a living as a teacher and wrote books, TV dramas and stage plays. In 1983, he was appointed to an executive position in Channel 4 TV. In his incarnation as commissioning editor for multicultural programming for Channel 4 (1984-97), Farrukh commissioned hundreds of hours of TV in all genres, including the Oscar nominated Salaam Bombay, Shekhar Kapoor’s Bandit Queen, and award-winning TV shows like Desmond’s and Family Pride.

And now, without any of my usual smart-ass comments – straight for the Farrukh Dhondy interview.

1. For the first time, what made you think you have a career in writing?

I decided at a very early age when I was in school and the youngest and feeblest in my class and when I tripped over the stick in the compulsory hockey game and was kicked about the compulsory football field and dodged the fast bowling in the nets, that I needed other ways of winning respect or even acceptance and self-confidence. I knew I could tell stories and began writing prose and poems in the school magazines, then in the college publications, then as a reporter in my teens, earning pocket money from it as a reporter for the Poona Herald – the new newspaper in the town in which I grew up. I was a paid journalist I thought, even though it was only ten rupees for an article.

I went to university in Britain and began contributing articles and columns to Indian newspapers including the Times of India and then Debonair. I thought of myself as a writer and after university came to London and got uncertain employment as a contributor to news agencies one of which Forum World Features paid me well but turned out, thirty years later to be exposed as a front for the CIA. So, they were using my, by and large left-wing, diatribes as a cover for their clandestine propaganda. Oh well.

I began writing for the left-wing immigrant groups of which I was a member and several editions of the very short stories I wrote about my experience as a school teacher a man in a suit approached me and asked for me in the staff room of the school I taught at. I went to the staffroom door and when he asked if I was Farrukh Dhondy, I asked him if he was from the police and when he said he wasn’t I asked him if this Farrukh Dhondy owed someone money he’d come to collect and he said no. He said he was from an establishment publisher and he had read my stories in the left-wing rag and wanted to know if I would write a book for Macmillan.

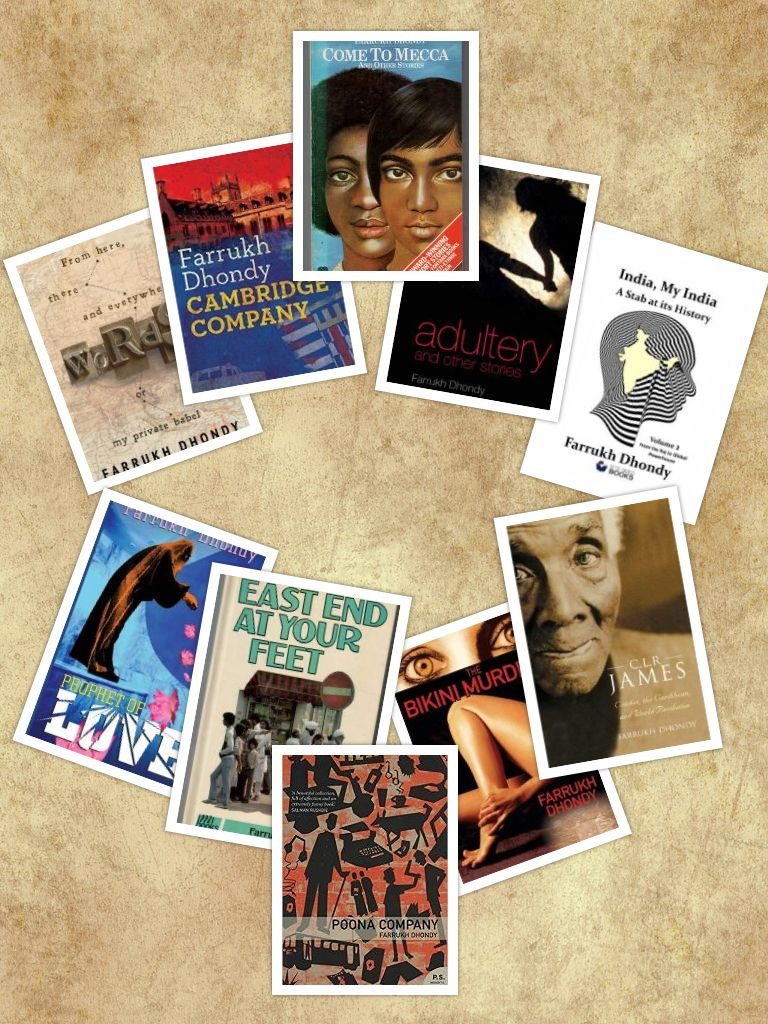

I agreed and, in a few weeks, sent them the manuscript of my first short story collection called East End at your Feet. After it was published the editors demanded the next book. It was a novel called The Siege of Babylon and based on the experience of being in Britain’s Black Panther Movement from which three young men broke loose to perpetrate an act of hostage taking. Their desperate act of holding up a restaurant for nine days, till the police crashed in and arrested them, became notoriously known as the Spaghetti House Siege. I turned my personal acquaintance with one of these desperadoes into the novel.

A year or so later I was using my crowded hours, apart from earning my living as a school teacher, to agitate and propagandise in political causes for the mainly Bangladeshi community of the East End of London.

From that experience my third book Come to Mecca was conceived and published. Right time, right place, right theme. Luck!

And then, apart from immediate observation, the second mine of writing—memory. I wrote about my early years, a sort of autobiography from the age of eight to twenty when I left my home town of Poona to go to Cambridge, England – to study physics. It’s called Poona Company.

2. How do you select your ideas / themes when you write? Is it a sudden burst of thought or a carefully evaluated decision?

I think the essence of writing is observation and spotting the thread of a narrative in the phenomena you are observing. The observation may not be conscious. It may accumulate over years and suggest itself then as a theme you wish to explore. Even if one is writing about oneself, its significance, however slight to the reading world has to be evident to me before I start.

3. How much of your personality and/or early experience as an activist influence your selection (or rejection) of ideas?

Everything I write comes from admiring and spotting the nuances of character, the flow of events and the depths of motivation manifest around me. Of course, genre writers, like Roald Dahl, JK Rowling or creators of modern myths such as Batman, write from regenerated tradition and innovation within a tradition. I have never done that. I seek to transform what I see and know and digest as important into narrative –autobiographical or fictional. Ideas should be incorporated into fiction — which should not spring from them. If the story comes from an idea, the danger is it turns into propaganda and loses the edge of truth.

4. Do you allow your ‘politics’ to shape what you write? The other way round, does your politics allow you to write whatever you want to?

No.

And yes.

5. The toughest thing is to start ‘writing’. I, for instance, always think of a title or a tagline first – and then build around it!! How does Farrukh Dhondy start his first words on a blank page?

The subconscious provides the stuff of fiction. A journalistic piece, a column, an essay, these very answers come from the conscious logical, memory-searching mind.

The subconscious which has been milling and mining a story thrusts a scene to the forefront of my mind as I sit at the typewriter (computer?) and then a description or dialogue forces itself on me. Obviously, if one is writing a film such as Bandit Queen, one has a list of events and progression of the character and these have to be incorporated as truthfully as possible.

But in writing a film one keeps in mind that it is not a novel – it’s a short story because the audience doesn’t come and go as from a book but sits there for about two hours. The technique, for instance in a biography, is to find the short story in the life – so with Abraham Lincoln, which I didn’t write and Mangal Pandey, which I did.

6. In longer formats, like screenplays and memoirs – do you create a structure first and then write? Or you keep reorienting the story as you move forward?

Screenplays and TV have to be plotted and planned. I usually write, strictly for myself, what I call a ‘sequence breakdown’ – always at first scribbled on paper and then refined onto the computer. I always think the whole screenplay or episode or series is in my head but discover, as I write the breakdown, that I am adding eighty per cent of the flesh of what it will become. Then I follow this pattern to do the whole thing.

7. My last question is again about writing screenplays – how has your comfort level in other forms of literary writing helped you in writing screenplays? Does a screenplay writer need to be a good reader as well??

The one thing I think a screenplay writer should do is stop watching films. Everything one writes should be from the eye and ear and mind and not from the imitation or modification of something you’ve seen. The “X film meets Y film” genre of the American lexicon is the worst possible way of initiating what you write and is the mark of a mediocre or even a non-existent ‘talent’.

A ‘log-line’ is the expression of the commerce of film-making with the pretence from Hollywood, and now Indian, producers and financiers that they have no time for the 20%-art that film is, but for the 80% -commerce that the creative form, of necessity, is.

I don’t know that reading assists screenplay writing—it must do, but the ability to visualise is perhaps a necessary skill – not that one should usurp the function of the director whose job it is to turn your words into moving pictures.

Finally, fuck ‘log-lines’ ‘arcs’ and ‘beats’. Write by twisting observation into plausible fiction – even if the genre is fantasy.

That’s solid advice; and applicable.

For me, I have always believed that a story has the potential to tell itself – be it fiction or otherwise. Your viewer demands your story to be interesting from zero minute – and that is why you have to allow the story to flow out of your guts, and not your brains. But yes, the outburst has to be conditioned – the mind needs to be prepared to monitor the guts. I believe that maturity comes from practice and patience.

Farrukh told in another of his interviews that the best stories have a dilemma right in the beginning, where the viewer wants to participate. The beginning is always about setting up the contours of this dilemma. And then, there’s a choice that arrives – which leads to consequences. The closing of the film is about the extensions of that consequence.

The best closings are those that gives us the expected, but in a rather unexpected manner.

Like life. The end is expected, but the best ones always will have a twist in the tail. Now that’s a fantasy that won’t happen automatically; we have to write it.

Right now I am reading Farrukh’s Company Trilogy… Poona, Cambridge and London Company.

Liked reading it.

Farrukh is good Nishi. Read his Company series … quite vivid and passionate.

Sound advice

Yaa, a bit quirky, but makes sense.

Enjoyed it…

Me too my friend…me too.

Nicely written.

Liked best- No. And yes. In the ambivalence, lies the answer.

Yes. Crisp but loaded.

Like!! I blog quite often and I genuinely thank you for your information. The article has truly peaked my interest.