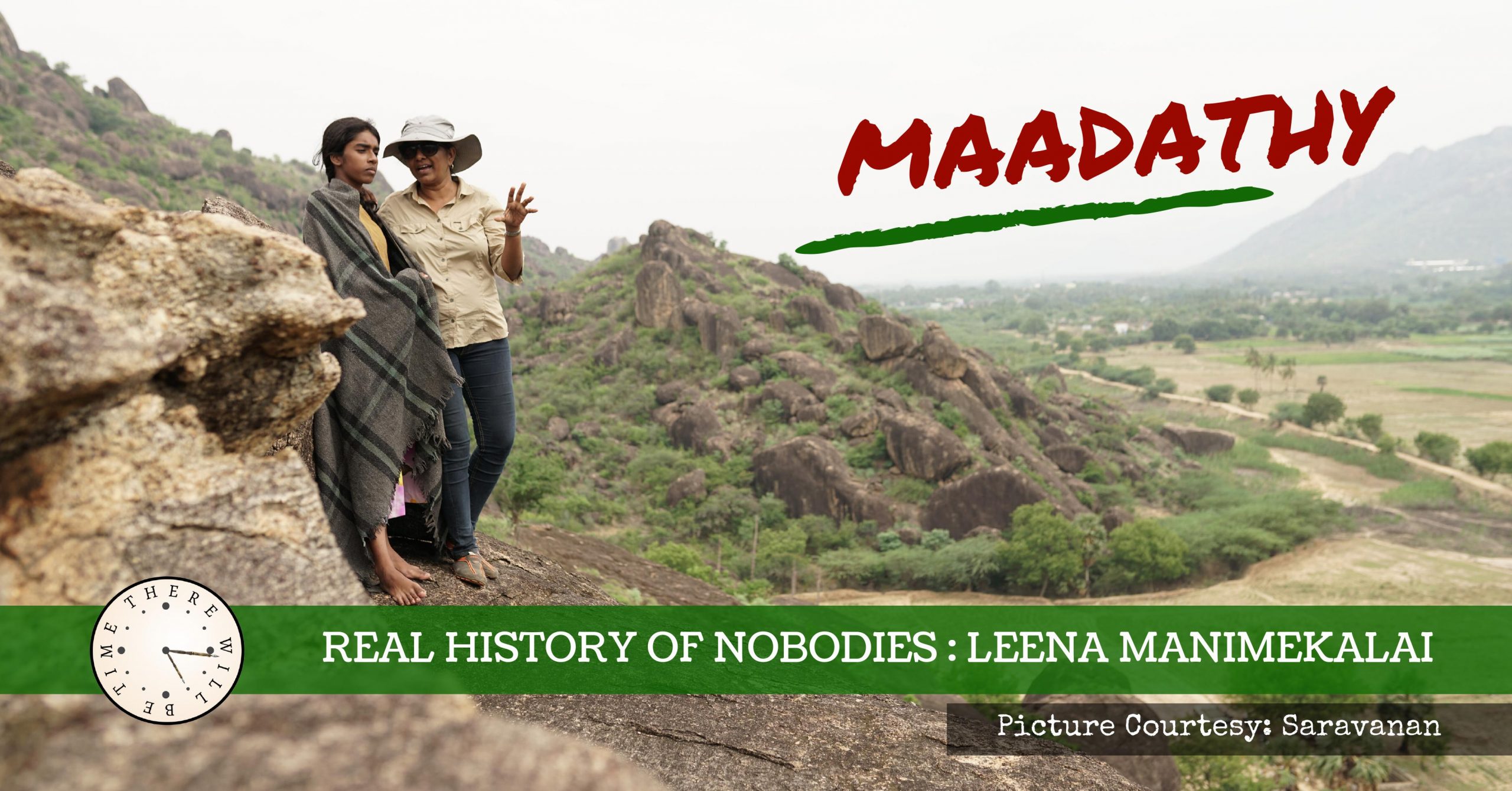

Right at the onset, let me get this straight, if you are looking for objectivity, then you are likely to be very frustrated with Leena Manimekalai.

Her films are her statements, often of rage. Hence, they hurt.

Nothing she has done so far is impersonal, at least not in the films of her that I have seen.

Leena’s documentaries like ‘White Van Stories’ on enforced disappearances in Sri Lanka and docu-features like ‘Sengadal’ on the plight of Tamil fishermen caught in the crossfire of the civil war – are the work of an auteur with an agenda.

Her non-conformity resounds in ‘Goddesses’, a documentary about three ordinary women who go against social conventions to live and work by their own rules; even the mockumentary she made on the house-hunting woes of two transgender friends, ‘Is it too much to ask?” has her unique stamp of no-nonsense, utterly pragmatic storytelling.

A ‘heart’ person with a political mind, she isn’t one who would want to conceal her emotions, or compromise with its expressions. Someone who doesn’t just make films, but feels them – Leena allows her subjects to define her voice.

That’s why watching Maadathy, her first pure fiction, becomes such a rousing experience.

The film is vintage Leena Manimekalai.

Maadathy is her love child.

Here, all her inherent rage has matured into something far more subtle, assertive, and expressive. The angst is all still there, but it’s all now neatly structured and subliminal – and that combination hits you real hard.

It’s never easy making a film that’s so outspoken and unusual.

For Maadathy, it became even more complicated, since the producer backed out midway, and Leena had to go for crowd-funding to complete the project. She used a Face Book fundraiser to raise money, and finally pitched for and won the finishing funds at the Singapore South Asian Film Festival to complete the film.

And then, after a bout of boxing with the censor board and a legal fight to get the film certified without cuts, and after a world premiere in Busan and Indian premiere in KIFF, Leena is now ready with the film.

On the surface, Maadathy is the mythical origin story of a subaltern deity – born out of death, oppression, extreme social isolation and injustice. But Leena doesn’t stop at that, and layers the film with various sub-texts. I could see reflections of her earlier thoughts in it all along, but the film in itself is a fresh, unique work of art.

It’s a legend, true; but with reality as its cornerstone, and underplayed anger as its primary narrative instrument.

Leena worked on the film with a small crew, using guerilla techniques. She engaged in participatory film-making involving lesser known theatre actors and members of the Puthirai Vannar community. Somewhat like what she did earlier, in Sengadal, involving the fisher-folk and the refugees of Dhanushkoti as actors and crew members.

Before any further details, a spoiler alert.

Since the film is awaiting its commercial release, I would rather say stop right here if you do not want to know more about the storyline. It’s been widely written about, by eminent film critics like Shoma A Chatterjee and Baradwaj Rangan – click on their names and read their opinions. There’s nothing I can add in terms of content that these stalwarts haven’t already done.

I would rather look at the film from a screenwriter’s outlook.

To me, much of the film comes across as a storytelling through contrasts – where the ugly reality of the outcast(e) family’s (and the protagonist’s) life gets juxtaposed to the pristine beauty of nature – through excellent camerawork, balanced edit and sound design.

In Maadathy, the growing up tale of a free-spirited nature loving teenage girl is pitted against the sexually loaded abuse of the young village boys and ugly fights over temple-funds. Here, rape happens against the divine backdrop of temple hymns to the mother goddess – there are many such studies in contrast.

Yet another important myth-making tool is the subtle hints that are strewn throughout the film; these lead to the crescendo – deification of an every-woman.

Lust is one such sub-text; right from the beginning, it’s there as an undercurrent – placed naturally as an everyday human behavioral streak. If you feel shocked by its casual depiction, it’s your problem, because it’s there, present, prevalent and naturally integrated in our social psyche.

Another critical storytelling tool is the teenage girl developing the female ‘gaze’ – also a natural occurrence that we often prefer sweeping under the carpet. Good girls do not gaze at men bathing in their full frontal glory. This girl, from an unseen caste, likes to ‘see’ – a feature she has in common with all girls her age, I presume.

To a large extent, her situation is that of the girls and women we know. They can of course ‘gaze’ at men, but they should not be seen doing that.

Yosana is a stalker as well, and a mischievous one – though the object of her desire has no idea that he is being stalked. I particularly loved the scene where she steals the shirt of her ‘crush’, wraps it around and runs through the grasslands – gloating in mirth and floating like a bird in a careless flight.

All of this makes you fall in love with her; which means, like her mother, you also start fearing for her. If I may say so, I have a daughter her age, and despite being from a privileged class, I know how it feels like bringing up a free-spirited teenage girl in our largely senseless, rabid and psychotic immediate world.

Multiply that manifold for Yosana’s mom, a severely victimized outcast(e) forced to stay in the bushes away from the sight of others, despised by all. She obviously has nightmares about the horrors that await Yosana.

The girl is forced to survive within the taboos that the majority has set for her. I feel, from that angle, the film becomes an universal parable for any social outcast, including the religious, gender and political ones.

The turning point in the film arrives when the mother of Yosana gets raped by a higher caste villager who lusts for her, but also refuses to see her face – and all the romance you have built till then for the atmosphere gets rudely jolted.

As you realize that this might not be the first time this is happening to her – that scene makes you ready for the eventuality – when fear, another recurrent theme emphasized by the mother’s constant worries for her daughter, finally starts taking over.

On the other hand, there are constant references to the eventual deification of the girl – like putting a parrot on her shoulder, making the grandfather throwing himself at her feet where he refers to her as Maadathy, her eating of the fruits meant for the goddess, the donkey taking her ravaged body to the temple – she is a myth in the making, across the length of the film.

So here, the real meets the surreal; the natural and the magical collate, leaving hints behind that something sinister (or divine) is about to happen.

It’s all the same anyways.

Divinity is the alter-ego of fear.

The husband Leena refers to is also an interesting storytelling tool – to connect the myth with the contemporary. The husband is from our time, and it’s through the eyes and ears of his young wife, we look at the story of Yosana turning into a goddess.

The way Leena and her team develop the character of teenage Yosana is truly absorbing. As you start entering her world tracking the paradox of her growing up as an ‘unseeable’; as you start connecting with the premonitions of her mother; as you engage with her innocence and longings and heartbreaks – you start feeling not for her, but with her.

That’s why, at the end, you not just start owning her horror of being gang-raped, including by the object of her desire – but also end up cursing your own blindness. There’s so much that we choose not to see.

Suddenly, you start feeling one with the final frame in the hanging pictures in the hut. It somehow feels right that the entire village turned blind, being cursed by the unseen. Now they can truly see nothing.

Yes, the contemporary husband is also there, among all the blind men and women of the village, but if you look hard in the crowd, you might even find yourself in it. I did.

In Maadathy, Leena has not pushed the agenda, but allowed the story to flow. That’s a significant departure from her earlier storytelling style.

Finally, it all comes together.

The girl that you have fallen in love with turns into a vengeful subaltern deity, a haunting spirit; hence the tagline, ‘Nobodies do not have Gods; they are Gods’

I did ask Leena, is it a period film? I was hoping it was, since I would, rather coyly, prefer to believe that such stories do not exist in our times.

She says, it’s not dated, since it’s a fairy tale.

I would add to that ambiguity. It’s also an epic poem, representing centuries of injustice that humans have inflicted on humans – keeping some sections of the society downtrodden, to benefit from them.

It’s those unheard voices of these unseen people that make Maadathy such a tough to ignore film. I leave you with some glimpses from the sets of Maadathy. Whenever you get to see the film, please see it. It won’t be like anything you have ever experienced before.

Leena has turned out to be a one of a kind independent filmmaker. Her imagination has a pull and I hope to watch her movies soon.

Thank for writing and sharing this unique blog with your readers Anirban. You continue to open up our perspectives.

Thanks for the response Saumya. I will keep track of Delhi Poetry Slam programs – and if there’s anything special happening please let me know. This time I will buy a ticket.

Excellent piece…

Wonderful piece! Have fallen under the spell of Leena Manimekalai (her name sounds so musical )! I wouldn’t have heard of her if not for your narrative. Yosana has sparked my interest, thanks to your sentient narrative.

[…] Well, Shoma-di did like my blog piece on ‘Madathy’. […]