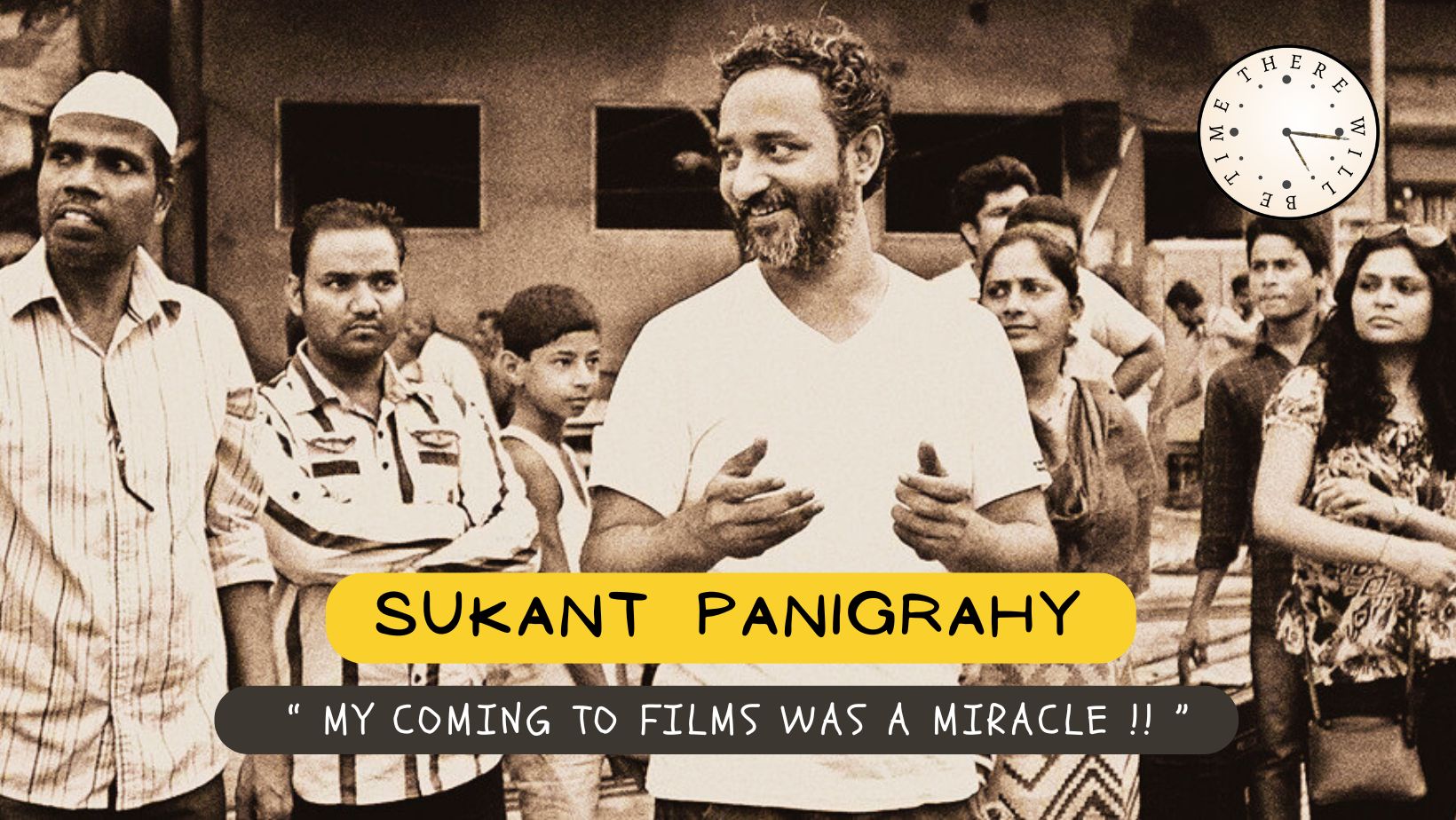

Sukant Panigrahy’s hustle with life could perhaps be best understood as osmotic. He did some odd things to make life happen, and life did some course corrections to make him happening – while all of this interactivity seeped across a thin diaphragm of uncertainty, always.

Or else, how else would you decode him? His phenomenon?

A boy from remote, backward Odisha with no formal training in art (or anything else) and with no direction in life turns out to become one of the most prolific, quirky, and celebrated Art Directors of Hindi Cinema. How?

I had been thinking.

I was on my way back from Sukant’s studio workshop in Mircholi village, Karjat, about 70 kilometres from Mumbai. I spent a night there, and took Sukant’s interview in a home that he has designed hands-on, out of waste collected from film sets – the Dodecahedron House.

I googled it. That’s the name of a geometrical shape – Dodecahedron, which is basically a polyhedron with twelve flat faces. The house is of that shape. When I asked him what on earth could be the reason to build a house with such a curious form – his response was simple. All our life we spend within the confinement of four walls. Maybe we can’t change the confinement part of it – but why can’t we change the number of walls? I wanted to live within more than four walls, so here is it.

Somehow, it made a whole lot of sense. But don’t ask me how.

An upright testimonial to the fact that maybe we can’t change life as it happens to us, but we can definitely make life happening, tweaking the way we look at it.

That’s Sukant. I think what makes him tick is his rock-solid outlook of positivity, personalized logic that he uses to determine his course of actions, quirky sense of humour, and never say never again approach towards destiny.

What makes Sukant Panigrahy different is his down to earth and stoic ‘attitude’.

I will not try to explain.

I would rather narrate his story exactly like he told me, and leave it for you to opine.

Sukant chose to be different.

He had no apparent reason to do that. Sukant belonged to a well-to-do family, with educated, and earning members. But he was never able to accept the repetitive structure in their lives. He explains – “You have studied so hard and achieved so much – have become a doctor, a Bank Manager, but still you continue to live in the same repetitive cycle, loaded with stress.”

That made Sukant feel, come what may, he won’t do a 9 to 5 job. By his own admission, he was okay with working 24 hours a day, but that has to be his wish, not a compulsion. He will never have a boss. That was how Sukant imagined himself during post-matriculation college.

I have known a few people thinking the same. Most of them compromise, when it comes to implementation. Not Sukant.

While roughing it out in Bhubaneshwar, Sukant had an inkling that his family might have traced him. That made him escape to Bombay.

Those were tough times. His everyday fell into a pattern. Roam around the streets, ask for manual work somewhere, earn enough to have food and go to sleep wherever the night allows you to lie down. Living on the streets caught up to him, and his life ceased to have any direction.

Living on the streets hurled at him all sorts of challenges, some of which he doesn’t even want to remember any more. But Sukant was determined that he will have to do something from within these conditions. What, he didn’t know.

Only one thing was for sure – that he won’t go back.

Don’t blame me if his interview sounds like neatly structured short fiction. That’s how Sukant Panigrahy tells his stories.

I interviewed Sukant twice, and the first time, due to a technical glitch, much of it didn’t get recorded. But I distinctly remember, the plot twists were the same the next time he was telling the same story, including the pauses. I had the feeling I am repeat viewing a drama, all over again.

Hence, excuse us if his ‘reality’ comes across as a neatly crafted stories, with defined beginnings and high points and endings with a twist. That’s just his craftsmanship which he can’t avoid. Sukant has the inclination and the disposition of a storyteller.

I believe it’s as true as anything could be. Structured truth.

A couple of days later, this school friend took Sukant to his and Dr Patnaik’s brother, Ajit Patnaik, an art director in the film industry. Ajit took Sukant in, even allowed him to stay at his house for a year. Sukant started learning the basics of art-direction under his tutelage.

Art direction happened to him by chance. At that point in time, Sukant was ready to do anything. He was just about seventeen years old and anything felt better than what he just went through. That apart, Sukant always had the creative bug towards building things, even while in school. That talent got a gush of wind under its wings.

Ajit Patnaik mostly did TV serials.

Sukant was good with the paintbrush, he was eager to learn, but the work he was getting was irregular – say about 5-6 days in a month. Rest of the days were free. Sukant kept earning and learning by taking up odd household jobs of film-actors and producers, usually offered to newbies because they came cheap.

Those days, he used to walk to work a lot to save money. Six rupees saved in fare means one half-rice plate, that was the calculation. While walking, he kept his eyes open for sign-boards that needed repair work, and asked for the job. He also tried his hand at painting number plates in a garage at one-third the market rates. Slowly, he started getting assignments to paint the entire truck, making good money out of it. Encouraged, he bought a few more brushes, started practicing his drawing skills. All of this boosted his confidence.

Sukant felt, he was now ready to level up.

That was when 18 years old Sukant started reaching out to Filmistan studios.

There’s a small temple there, which was created for a set, but had eventually turned into a marketplace for daily-wage workers. Every morning, around 7-8 AM, a variety of workers used to come there and wait. Anybody required any helping hand at the floor, they used to come and ask for it, and take their pick from the available skillsets there.

Sukant went there for two three days. He got to know from others that some SRK film is happening. A Yash Chopra film was also on the works.

He started dreaming big. This is where he wanted in.

This luck-by-chance became the launch-pad for Sukant.

People started talking, and those talks reached Sharmistha Roy – the art director of DDLJ. She is the daughter of Sudhendu Roy – and the sequence for which Sukant made the sofa was his set.

Now Sudhendu Roy was the undoubted big-boss of set-design and art-direction. Best known for his realistic sets in Bimal Roy films like Sujata, Bandini, and Madhumati, he was also a regular with glitzy Yash Chopra and Subhash Ghai films. A winner of three Filmfare awards, Sudhendu Roy set yardsticks with his work in films like Karz, Karma and Kaala Patthar.

Sudhendu Roy was quite old by then. He didn’t come to the sets. It was his daughter Sharmistha who carried forward her father’s mantle. DDLJ was Sharmistha’s magnum opus, as an independent Art Director. She met Sukant on the sets of DDLJ, and, impressed by his passion and skills – continued to give him work.

Starting with the DDLJ set, Sukant worked with Sharmistha Roy for around eight years.

After DDLJ she was flooded with all the top offers with top directors. Mahesh Bhatt, Subhash Ghai, Indra Kumar – all their films were with her. And she had such a large unit, that it was never a problem doing three films at a time.

Which also meant, Sukant was never free. She kind of trained him to take up one area – like anyone could erect the basic set, but what after that? What will be the colouring treatment after that – she used to discuss that with Sukant? Asked him to choose between colours. In the process Sukant learnt the names of so many different shades.

Back-to-back work with tough deadlines.

Sukant even had to be hospitalized once, for dehydration – since he insisted to complete his work and then go home.

During these 6-7 years while assisting Sharmistha Roy, Sukant also did a film appreciation course with filmmaker Ashok Rane, a multiple National Award winner for documentary films.

In that two-day workshop, he saw ‘Pather Panchali’ for the first time.

By his own admission, he had no idea that such films exist. The film blew his mind – this is also how a story can be told. People make films with such levels of passion, such craftsmanship – all of this was new to him.

The urge to become a film-maker started taking centre stage all over again.

Sukant wanted to move out, but Art Direction was in no mood to leave him alone – work kept coming. He thought of leaving Mumbai to avoid this.

By that time, he had made an animation storyboard. To make the film, he started talks with animators. They told him – to master the craft, he needed to get inside the domain and learn hands-on. Sukant went to Chennai and joined as an apprentice in an Animation studio.

While in Chennai doing the course, he was constantly in touch with Sharmistha Roy. One of those days, Sharmistha informed him that Subhash Ghai was asking for him. Sukant had worked for him in Taal.

Back in Mumbai, Sukant met Subhash Ghai and expressed his desire do something good in the area of animation. To do that, he and his team needs to go to Los Angeles to learn the craft better. The deal could be, after returning, they can work exclusively for Mukta Arts.

Subhash Ghai agreed to sponsor Sukant and his team.

Desperate to escape from the job security of Whistling Woods, Sukant went and met Prakash Jha. At that point in time, Prakash Jha had a series of flops, so he wanted to tread his path rather cautiously. Gangajal was not supposed to be a big film. It had limited budget.

Prakash Jha has seen Sukant work as Sharmistha’s assistant in his previous films like ‘Dill Kya Karein’ and ‘Mrityudand’. He knew what Sukant was capable of. Other Art Directors he approached were either not interested, or apprehensive of the budget.

Sukant, on the other hand, was desperate for a chance.

Those thoughts remained with Sukant Panigrahy.

Much later, while at the top of his game, he took significant efforts to make working conditions better for menial labours who painstakingly erect those magnificent structures that form the backdrop of our cinema.

He knew he was going to make enemies, but yet, at his peak of career, Sukant spent 7 years in strengthening a labour union as its President – the Art and Costume Union. And yes, he did ruffle a few feathers and lost a few projects, branded as the union guy.

Even while working with Sharmistha, Sukant ran a self-sponsored NGO to teach slum kids, helping them nurture their talents. When the excesses of the industry aggrieved him, he used the waste to build accommodation for the poor.

Sukant has also created numerous studio and outdoor installation-art pieces, using e-waste, to generate awareness among people about the threat e-waste poses on our environment.

With Sukant, when a thought arrives, it leads to action. Some of these actions might seem like banging your head against a concrete wall, but that’s how it is. That’s who he is.

But yes, he also created backdrops for films that are now considered to be cult-classics. Ranging from the harsh realism of ‘Drishyam’ to the surrealism of ‘Dev D’, from the funky world of ‘Tashan’ to the tense thrills of ‘Ek Tha Tiger’ to reliving the past with ‘Manikarnika’ – he has been everywhere, at ease.

More of that later, in our second and final part.

As an epilogue to this, I really need to thank my readers for continued support.

Somehow, despite my irregularities, this long-format blog is continuously attracting traffic. And what makes me feel smug are my top-hit posts, on Kumararaja and Gautam Chatterjee. I believe it’s high time I did another post on Gautam-da.

As soon as possible.

Be First to Comment